Sacred vs. Secular vs. Christians

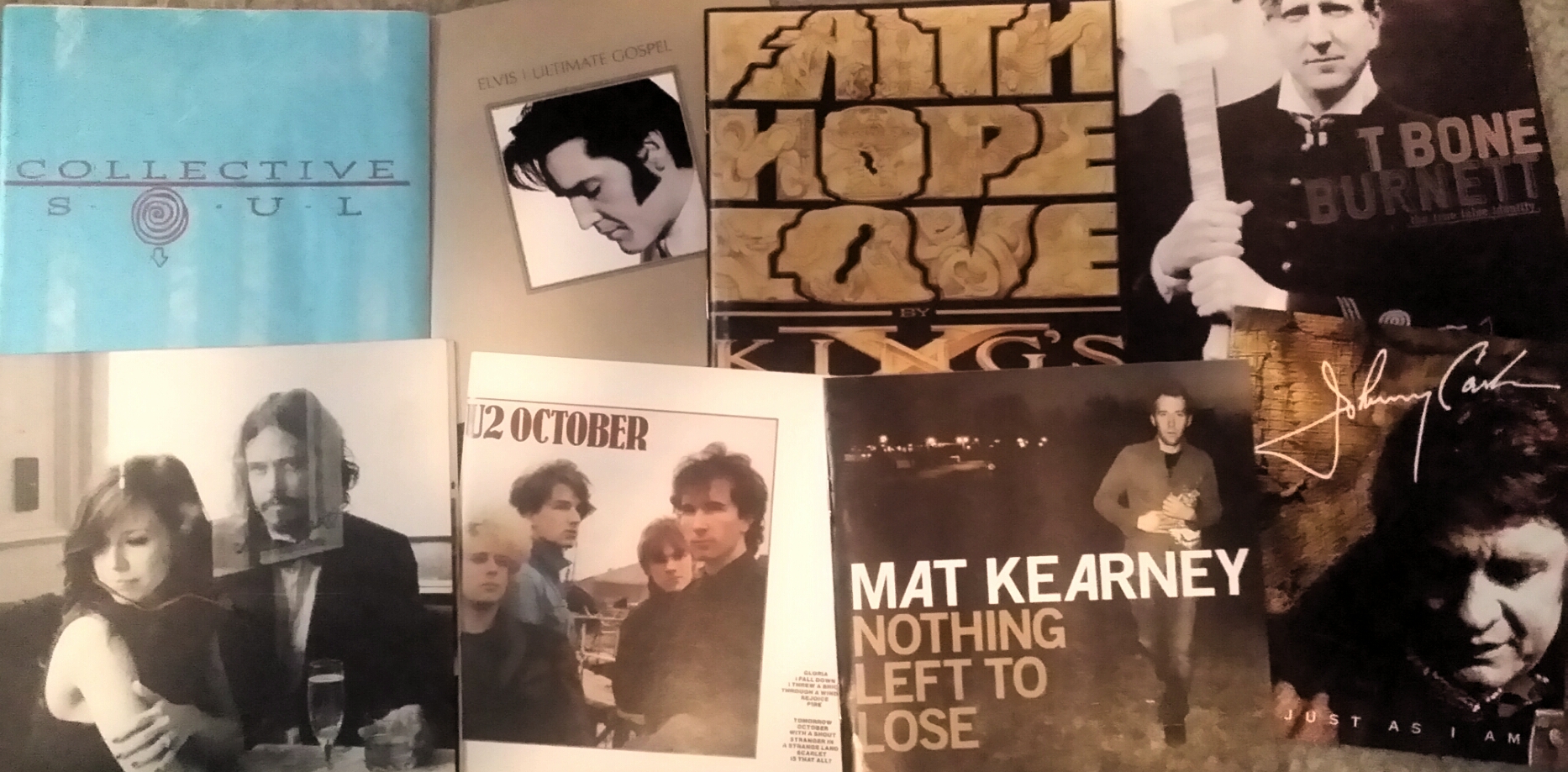

Over the past couple of years, I’ve been involved in a group in social media that celebrates a major part of my youth/teen years: 1990’s Christian music. In discussions we have in this group, one debate continual comes up: what artists/bands/songs/records qualify for discussion in the group…in other words, what qualifies/defines “Christian music”. Of course, one solid argument is that since music cannot be saved/redeemed, that Jesus didn’t die for music, and music doesn’t go to heaven or hell, then music can’t really be “Christian”. But what about a “Christian musician”? Does one have to meet certain lyrical content requirements to be considered a “Christian artist”? What about instrumental artists, who make music without lyrics? Not to mention that in the late 90’s we saw a movement of music and claiming to be “Christians in a band…NOT a Christian band”. Is there even a need to define music or artists as specifically Christian? Is it necessary to separate the sacred from the secular?

Over the past couple of years, I’ve been involved in a group in social media that celebrates a major part of my youth/teen years: 1990’s Christian music. In discussions we have in this group, one debate continual comes up: what artists/bands/songs/records qualify for discussion in the group…in other words, what qualifies/defines “Christian music”. Of course, one solid argument is that since music cannot be saved/redeemed, that Jesus didn’t die for music, and music doesn’t go to heaven or hell, then music can’t really be “Christian”. But what about a “Christian musician”? Does one have to meet certain lyrical content requirements to be considered a “Christian artist”? What about instrumental artists, who make music without lyrics? Not to mention that in the late 90’s we saw a movement of music and claiming to be “Christians in a band…NOT a Christian band”. Is there even a need to define music or artists as specifically Christian? Is it necessary to separate the sacred from the secular?

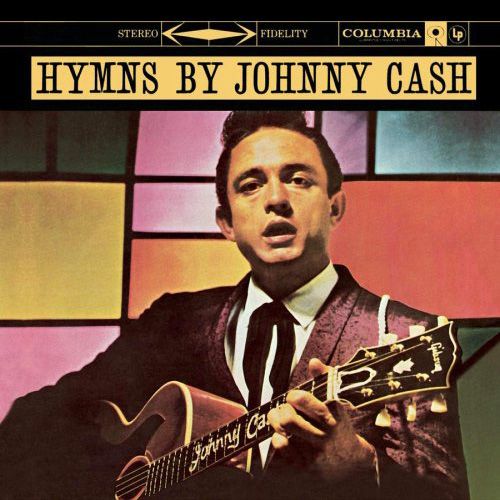

If we trace the origins of what we now call Contemporary Christian Music, we see that it was originally rooted in what was called “Gospel Music”. Today, when we think of Gospel music, we tend to think of a specific style of jubilant, not quite rock and roll, music associated with African-American churches, that had a deep influence in R&B. However, initially the label “Gospel music” referred to just about any music with a specific Christian or Gospel message. The recording of Gospel music  dates back to the earliest days of recorded music by artists like The Carter Family. Of course, the earliest country, or hillbilly, music was really a merging of Appalachian Folk, Blues, and Gospel music, and it was common for popular country artists to make Gospel records. In fact, one of the reasons why Johnny Cash left Sun Records for Columbia, was that Sam Phillips wasn’t keen on Johnny making Gospel records and Columbia was willing to allow him to make a full Gospel album. As a genre/market Gospel music included Black Gospel like The Five Blind Boys of Alabama, mainstream artists turned Hymn singers like Tennessee Ernie Ford, and Southern Gospel Quartets like The Imperials.

dates back to the earliest days of recorded music by artists like The Carter Family. Of course, the earliest country, or hillbilly, music was really a merging of Appalachian Folk, Blues, and Gospel music, and it was common for popular country artists to make Gospel records. In fact, one of the reasons why Johnny Cash left Sun Records for Columbia, was that Sam Phillips wasn’t keen on Johnny making Gospel records and Columbia was willing to allow him to make a full Gospel album. As a genre/market Gospel music included Black Gospel like The Five Blind Boys of Alabama, mainstream artists turned Hymn singers like Tennessee Ernie Ford, and Southern Gospel Quartets like The Imperials.

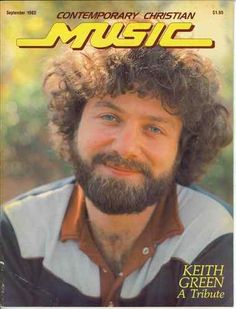

As rock and roll and pop music grew in the 1960s and 1970s, Gospel music continued to grow and change. Some artists, like The Staple Singers and Oak Ridge Boys, went on to more ‘secular’, mainstream success, while other artists, like The Impressions, found popularity by merging a Gospel message with the civil rights movement. And there were a number of secular artists that sang songs that seemed to convey a somewhat Christian message in their lyrics, such as Turn Turn Turn, Spirit In The Sky, and Get Together. But by the end of the 1960’s, there was definitely a new development of “Jesus Music” growing out of the Jesus People movement of hippies becoming Christians. This trend is what eventually came to be known as Contemporary Christian Music or CCM.

Through the 70s and 80s, CCM came into its own as a niche market and radio format. It generated its own magazines and other media outlets, and established a number of major Christian record labels and even a growing underground scene and independent record labels. For much of this time, CCM recordings were known for being behind the times and lacking production and artistic quality, but as the market’s popularity rose, bigger budgets meant better production and Christian artists were beginning to push artistic and creative boundaries. But no matter how popular and accepted Christian music became, there always seemed to be a separation isolating it from ‘secular’ music.

To a large degree, this was the fault of the CCM market itself and the religious  audience that had nurtured its success. Many Christians held a fear of secular music; so they would avoid listening to anything but CCM, and expected Christian artists to maintain a blatant message to help make the distinction easier. So the record executives and ‘gatekeepers’ of the industry pushed the ‘Jesus quota’ standard and often imposed restrictions or a ‘glass ceiling’ on the artistic and creative pursuits, trying to make sure that most Christian artists retained a certain sound or feel to keep the Christian audience satisfied and loyal. Christian musicians and artists had worked hard to create a place where they could express their faith openly, because the mainstream ‘secular’ market supposedly rejected music with too blatant of Christian message and lyrics, but now it seemed like they also had to fight the CCM industry to have the freedom to express something outside of a simple, shallow gospel message.

audience that had nurtured its success. Many Christians held a fear of secular music; so they would avoid listening to anything but CCM, and expected Christian artists to maintain a blatant message to help make the distinction easier. So the record executives and ‘gatekeepers’ of the industry pushed the ‘Jesus quota’ standard and often imposed restrictions or a ‘glass ceiling’ on the artistic and creative pursuits, trying to make sure that most Christian artists retained a certain sound or feel to keep the Christian audience satisfied and loyal. Christian musicians and artists had worked hard to create a place where they could express their faith openly, because the mainstream ‘secular’ market supposedly rejected music with too blatant of Christian message and lyrics, but now it seemed like they also had to fight the CCM industry to have the freedom to express something outside of a simple, shallow gospel message.

By the 1990s, CCM and Christian rock had become a major force in in the music industry. It was apparent that the mainstream/secular industry was taking notice of CCM’s success, and even signing Christian artists to joint deals with distribution in and outside of the usual CCM market. Eventually Christian artists like Amy Grant, Michael W Smith, and Sixpence None the Richer were able to rise out of the CCM “ghetto” to have number 1 mainstream hits. And as Christian artists began to experience greater acceptance in the bigger mainstream ‘pond’, they were also finding greater acceptance within Christianity. After decades of The Church condemning rock music and the similar sounding CCM, those in ministry and authority were finally seeing the potential of Christian rock music to reach people that other forms of ministry couldn’t.

But this idea of Christian rock as ministry seemed to lead to more separation between CCM and secular music. There were a few bands that had established themselves outside of the CCM market, but were embraced by Christian audiences because of the members’ faith and lyrics hinting at that faith, but many of those bands weren’t interested in being too closely associated with the Christian music scene or the expectation of ministry implied in Christian music. Also, many artists within the CCM industry began taking issue with the expectations of blatant Jesus-y lyrics and music as ministry, including expectations of mini-sermons and altar calls from the stage. There was a movement to try and integrate more Christian artists into the mainstream market, and to allow those artists more freedom to express themselves, their faith, and lives beyond a blatant gospel message, but it seemed that Christian audiences were often confused by more vague lyrical content, or even lyrics that contained language or content that some Christians disapproved of. In this confusion, it seemed that the more Christian artists fought to get away from the expectations and standards of the CCM market, they were still facing some of those same battles with their audience. In response to this, a number of artists that had originally been established in the CCM market, began making claims of being “Christians in a band…not a Christian band”. Yet many of those bands were still deeply involved in the Christian music market and especially Christian music festival circuits, which just added to the confusion.

By the end of the 1990’s the major mainstream/secular record labels were buying up all of the Christian record labels. At first, that seemed like a positive step, because it pointed to even greater acceptance of Christian music within the larger mainstream market. But, early in the 2000’s it seemed that the entire CCM scene and market had changed drastically. Many of indie labels in the Christian market disappeared, as did many of the more ‘fringe’ artists that had become Christian alternative’s critical darlings. It was beginning to feel like all of the hard work and progress that the CCM scene had made through the 80’s and 90’s was being discarded, as the blatant message and artistic limitations once again became the focus of Christian music. Christian radio started focusing on being “safe for the family” and practically every song heard on that “safe” radio sounded the same, and void of artistic integrity or genuine passion.

Of course, the whole music industry was changing and struggling due to the internet and ease of digital downloading. But Christian music seemed to take a much harder hit, at least from the perspective of us as fans and consumers. Nearly every thing that we had loved about the scene seemed to disappear, and we felt the industry had discarded us in favor of a whole new Christian audience. And worst of all, it seemed that the wedge between Christian and ‘secular’ music had been driven even deeper.

Sure, there are more artists within the secular/mainstream market than ever, revealing and sharing elements of faith and Christianity in their music, but these artists seem even more removed from the Christian music industry. On one hand, this can feel like a success for Christians making music…to be accepted as legit artists without trying to be big fish in the little pond of CCM. But on the other hand, it feels like we’ve lost something within the Christian music industry that we had felt proud of, that we could relate to and passionately share with the rest of the world. Now, it seems harder than ever to convince non-Christians that Christian music can be just as good and artistic as secular/mainstream. I guess that if we’re honest, the whole time we wanted the rest of the world to accept our attempts at Christian music, we never really intended our little niche/scene to completely disappear as it was absorbed in the bigger ‘pond’ of the mainstream market.

Obviously, Christians have been making and recording music, as long as there has been music. This label of “Christian music” is a relatively recent thing, and there certainly is a strong argument that there is no need to differentiate Christian music, from ‘secular’. Maybe, for those of us who grew up on CCM, it’s just an old, hard dying habit of distinguishing Christian artists from specifically non-Christians. Or maybe, there is a deeper connection beyond just labeling music as either religious versus secular. For me, I’m always looking for music that I can connect with spiritually, as well as artistically and aesthetically. I feel like the more I know about an artist’s faith, the more I can connect and relate to their music and artistic expression. It’s not that I’m looking for a specific ‘Jesus quota’ in the lyrical content…just that a faith-based, spiritual connection ultimately brings me deeper satisfaction in my listening experience, and can have an impact on my own spiritual walk. Not that I don’t listen to secular music. Especially as CCM has grown further away from what I once appreciated about it, I find myself listening to more and more non-Christian music. But I still desire to find new Christian music that I can relate to on a much deeper level…but it’s getting harder and harder. I guess that, for me, it’s less about the separation between sacred and secular, and more about recognizing the faith and spiritual expression of fellow believers.

Obviously, Christians have been making and recording music, as long as there has been music. This label of “Christian music” is a relatively recent thing, and there certainly is a strong argument that there is no need to differentiate Christian music, from ‘secular’. Maybe, for those of us who grew up on CCM, it’s just an old, hard dying habit of distinguishing Christian artists from specifically non-Christians. Or maybe, there is a deeper connection beyond just labeling music as either religious versus secular. For me, I’m always looking for music that I can connect with spiritually, as well as artistically and aesthetically. I feel like the more I know about an artist’s faith, the more I can connect and relate to their music and artistic expression. It’s not that I’m looking for a specific ‘Jesus quota’ in the lyrical content…just that a faith-based, spiritual connection ultimately brings me deeper satisfaction in my listening experience, and can have an impact on my own spiritual walk. Not that I don’t listen to secular music. Especially as CCM has grown further away from what I once appreciated about it, I find myself listening to more and more non-Christian music. But I still desire to find new Christian music that I can relate to on a much deeper level…but it’s getting harder and harder. I guess that, for me, it’s less about the separation between sacred and secular, and more about recognizing the faith and spiritual expression of fellow believers.

I’m certain that there is a lot of sentimental nostalgia tied up in my disappointment over what has happened to the Christian music industry. I plan on writing about the details of what I, and so many other Christian youths, loved about our time and experiences in the peak of the Christian rock phenomenon, and what many of us miss about that time and scene. But like I said, I feel like there is more to “Christian music” than just a label or a distinction from the secular…more than a blatant message or including the name of Jesus in the lyrics. I believe that it’s about a spiritual connection, to the artists and to the art. I believe that if we, as fellow Christians, use this powerful medium of music to connect and fellowship, we can give our Creator more glory.