The Cinephile Files: Luke Takes on FANTASTIC PLANET

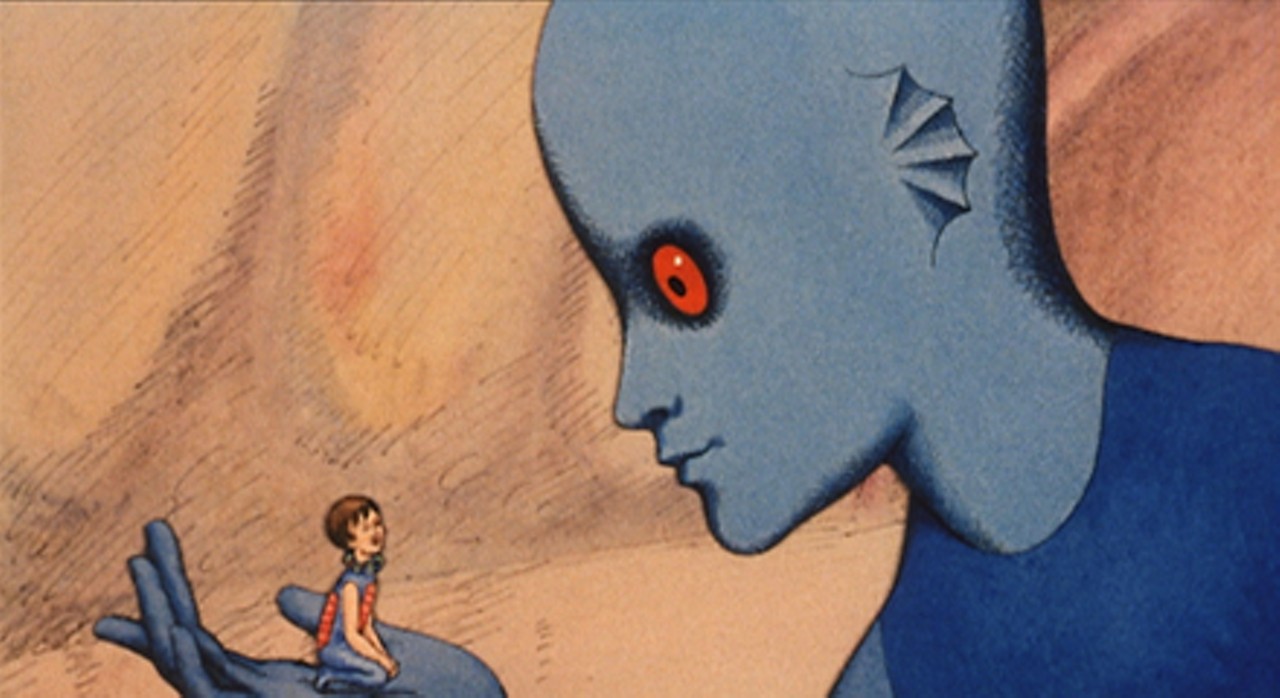

A woman, half naked, clutches a baby to her breast as she runs terrified through a strange, otherworldly landscape. She is pursued by a giant blue hand, blocking her escape at every turn. It is toying with her. After flicking her down with a cruel boredom, the hand lifts her up into the air and drops her, where she dies at arm’s length from her infant son.

This is our introduction to the planet Ygam, a world simultaneously savage, whimsical and surreal. The blue hand belongs to a Draag child. The Draag are giant blue humanoids with bald heads, red eyes, and fins for ears. They are the dominant species on Ygam. They possess advanced technology, and spend their days in meditation. The woman and child belong to a tiny race of humans, the Oms (a play on the French homme, for “man”). The Draags domesticate and keep Oms as pets… when they aren’t gassing colonies of wild Oms to the brink of extinction in an effort of population control.

Recently given a new 2K remaster by the Criterion Collection, Fantastic Planet is the feature debut of René Laloux, a filmmaker ripe for rediscovery here in the U.S. Originally released in 1973, made in collaboration with illustrator and surrealist Roland Topor, it remains one of the most singular science fiction visions ever put to film. Using a technique of cut-out stop motion animation, the film has a distinctly hand-painted look. It’s a free-flowing series of surreal imagery, continually surprising, that has not diminished in potency in the forty three years since its original release. All set to a great jazz-fusion score by Alain Goraguer, full of lush orchestration, vibraphone, wah wah guitars, and swirls of analogue synthesizers.

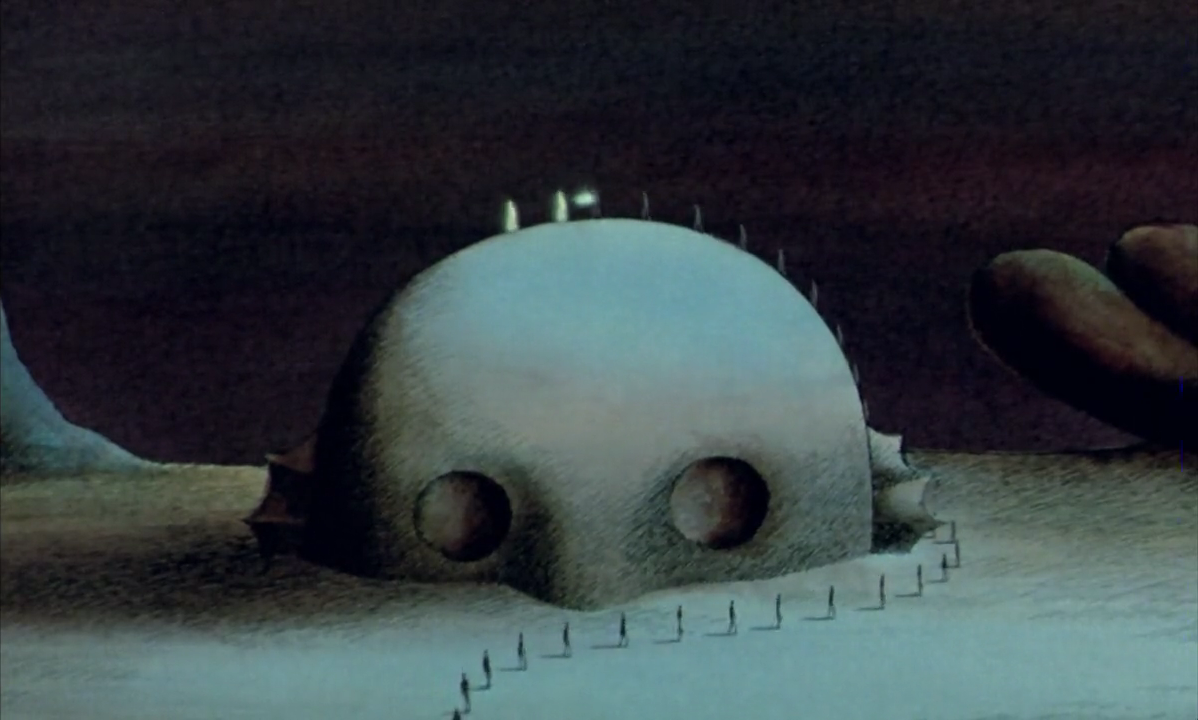

There might not be a much story to fill the film’s already brief running time. It’s an allegorical parable about a young Om named Terr, raised as a pet by the Draag girl Tiva. He grows up, escapes, and joins a tribe of wild Oms, where he attempts to use his advanced knowledge to help save the Oms from extinction at the hands of the Draag. The allegorical element and the characters may be a little simple. Its political message feels a little dated at times (the film was produced in Prague during the Soviet invasion of Czechoslovakia in 1968). But none of that ultimately matters that much. The heart and soul of Fantastic Planet lie in its detours, and fantastical asides: images of weird phallic eyeball crabs crossing barren landscapes; the Oms’ luminous midnight strip-tease ritual; the repeated images of the savage life-cycles of fantastical predators and prey; dancing statues on the moon; the hundreds of red and blue Draag meditation bubbles floating through the sky; even the planet Ygam itself breaths and pulsates like a biological organism. Fantastic Planet is a whole lot of psychedelic weirdness for its own sake, and it doesn’t let narrative or structure get in the way of its free-flowing visual poetry. And Therein lies the power of animation; to create images and worlds that could not be brought to life in any other way. Freed from the restrictions of reality, animation creates a vivid unreality that resonates with the imagination.