Viewer Discretion is Advised: Top 5 Pre-Film Disclaimers

If you’re old as dirt (like me), you may recall a time when the fine folks at the MPAA (or BBFC, or whatever) used to go out of their way to purge films of any potentially harmful material. Nowadays you can watch A Serbian Film on the Disney Network, so it might be hard to imagine a time when the general consensus was that a British person catching a glimpse of a nunchaku would invariably lead to an epidemic of ninja attacks on the… let’s say lorry.

However, some of these disclaimers were added by those involved with the films in order to prepare the audience for what was to come or get them in the proper mindset. Here are five of my favorite..

Yes, I know the title says “top”, but you’re here now. Keep reading.

The Last Waltz (1976) / Driller Killer (1979)

I grew up on the tiny, remote island of Newfoundland, and the audio in our local multiplex was tinny and hollow until the year 1994.

Why do I remember 1994? Because that’s when I saw the movie Stargate, which the cinema decided to use as some sort of sadistic experiment to see how loud the audio could be before people complained. It turned a (let’s face it) fairly middling Roland Emmerich movie into a carnival ride of excitement and ear pain.

That was the first time I realize that sound could make or break a movie, which is why I appreciated Martin Scorsese’s direction to potential projectionists – and, ultimately, home audiences – to blast the audio of his legendary concert film The Last Waltz. Even better was Abel Ferrara nicking the idea for his 1979 non-pornographic film debut The Driller Killer.

The disclaimer made a welcome return last year in Joe Begos’ Scanners tribute The Mind’s Eye.

Thriller (1983)

Look, we can argue until the cows come home over whether Thriller should be considered a movie. It had a movie budget, a movie director at the helm, and Rick fuckin’ Baker providing make-up effects, so the fact that it was only 13 minutes long and showed exclusively on MTV will be conveniently ignored. It had closing credits, damn it.

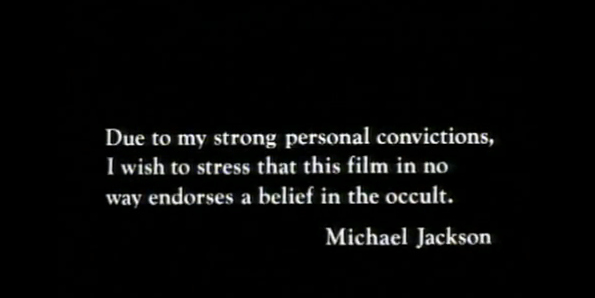

But what can’t be ignored is the truly bizarre disclaimer which begins the video, which carefully explains that Michael Jackson does not believe in ghosts. Or zombies. Or people in letterman jackets turning into werewolves.

Why he thought a goofy (but awesome) video featuring a Vincent Price “rap” and impeccably choreographed zombie dancing required such a pre-apology is a mystery. But apparently Jackson was so horrified by the results that he went even further and apologized to the entire world for scaring their socks off in the pages of Awake! Magazine, where he even stated he tried blocking its release in some areas of the world.

I don’t want to be speak out of turn, but that Michael Jackson guy sure was a weird dude.

Hollywood Chainsaw Hookers (1988)

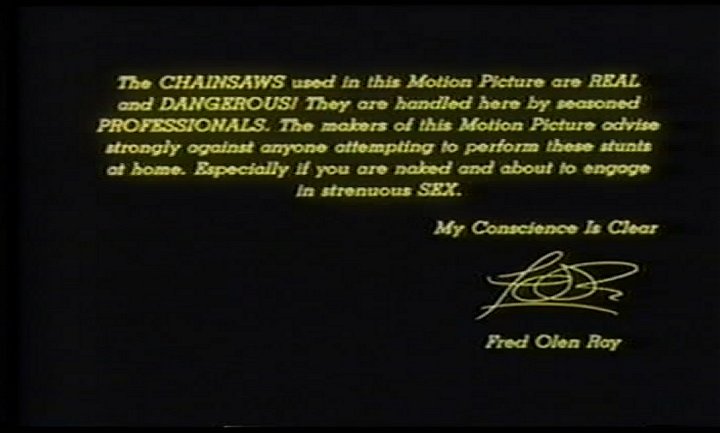

Years before Fred Olen Ray was specializing in Christmas-themed TV dramas, he and Jim Wynorski were having a contest to see who can make some of the strangest (and cheapest) sci-fi and horror of the 1980s. Ray reached his simultaneous apex and zenith with the delirious 5-day-wonder Hollywood Chainsaw Hookers, with its truly bizarre mixture of blood, boobs and film noir.

Since the film barely lasts 75 minutes, Olen Ray had plenty of time to insert a tongue-through-cheek warning to start things off, suggesting that unless you’re a professional, chainsaws and sex do not mix.

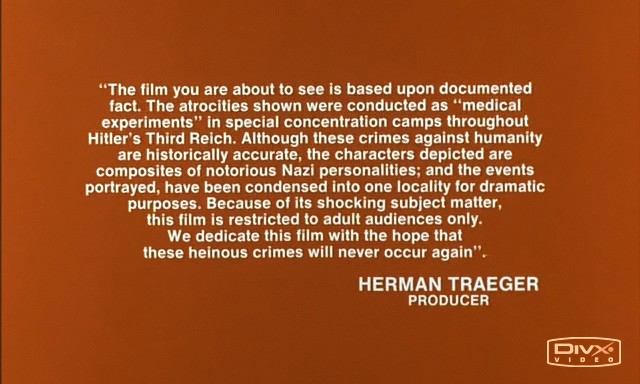

Ilsa: She Wolf of the SS (1975)

The first exploitation movies were usually marketed as instructional and/or moralizing films, with topics like drug use, teen pregnancy and general horniness meaning that the filmmakers could show all that wonderful stuff, while still making you feel appropriately bad about it at the end.

Producer David Friedman certainly knew a thing or two about squeezing T&A and violence through pre-70s content restrictions. After all, this was the man who helped create the original gore classic Blood Feast. But by 1975, the goalposts on what was and was not appropriate on cinema screens had significantly shifted, so when Friedman was helping put together his take on both the burgeoning women-in-prison and Naziploitation genre, he knew he had to go a bit further.

Despite its somber tone, this text from Herman Trager (actually Friedman) is pure bad-taste cheese, with its white text on red background promising plenty of violence, and Hitler himself leading a cacophony of “Seig Heils” on the soundtrack. As with Olen Ray, Friedman – and the audience’s – conscience was now clean. So bring on the perversity.

Dr. Strangelove or: How I Learned to Stop Worrying and Love the Bomb (1964)

Now that the threat of semi-imminent nuclear war once again hangs over our heads like the sword of damocles, we can again start appreciating just how horrifying Stanley Kubrick’s cold war black comedy masterpiece must have been to 1964 audiences. This was only a few years after the “Bay of Pigs” incident, and mere months after the assassination of John F. Kennedy (the film was actually delayed because of JFK’s death, and a line in the film referring to Dallas, Texas had to be removed), so the idea of an apocalyptic comedy must have been a bit of a hard sell.

Audiences were also treated to this stern disclaimer as the film begins:

It is the stated position of the United States Air Force that their safeguards would prevent the occurrence of such events as are depicted in this film. Furthermore, it should be noted that none of the characters portrayed in this film are meant to represent any real persons living or dead…

These words I’m sure provided cold (war) comfort for moviegoers at the time, but Kubrick was smart enough to break any potential tension with near-pornographic scenes of planes refueling in the air while the opening credits rolled. That mix of the deadly serious and the broadly comedic would go on to define the film, which despite its absurd dialogue and characters remains alternately hysterical and chilling.