A Tribute to Horror’s Least Beloved Character

Franklin’s horoscope in The Texas Chain Saw Massacre reads:

Travel in the country, long–range plans, and upsetting persons around you, could make this a disturbing and unpredictable day. The events in the world are not doing much either to cheer one up.

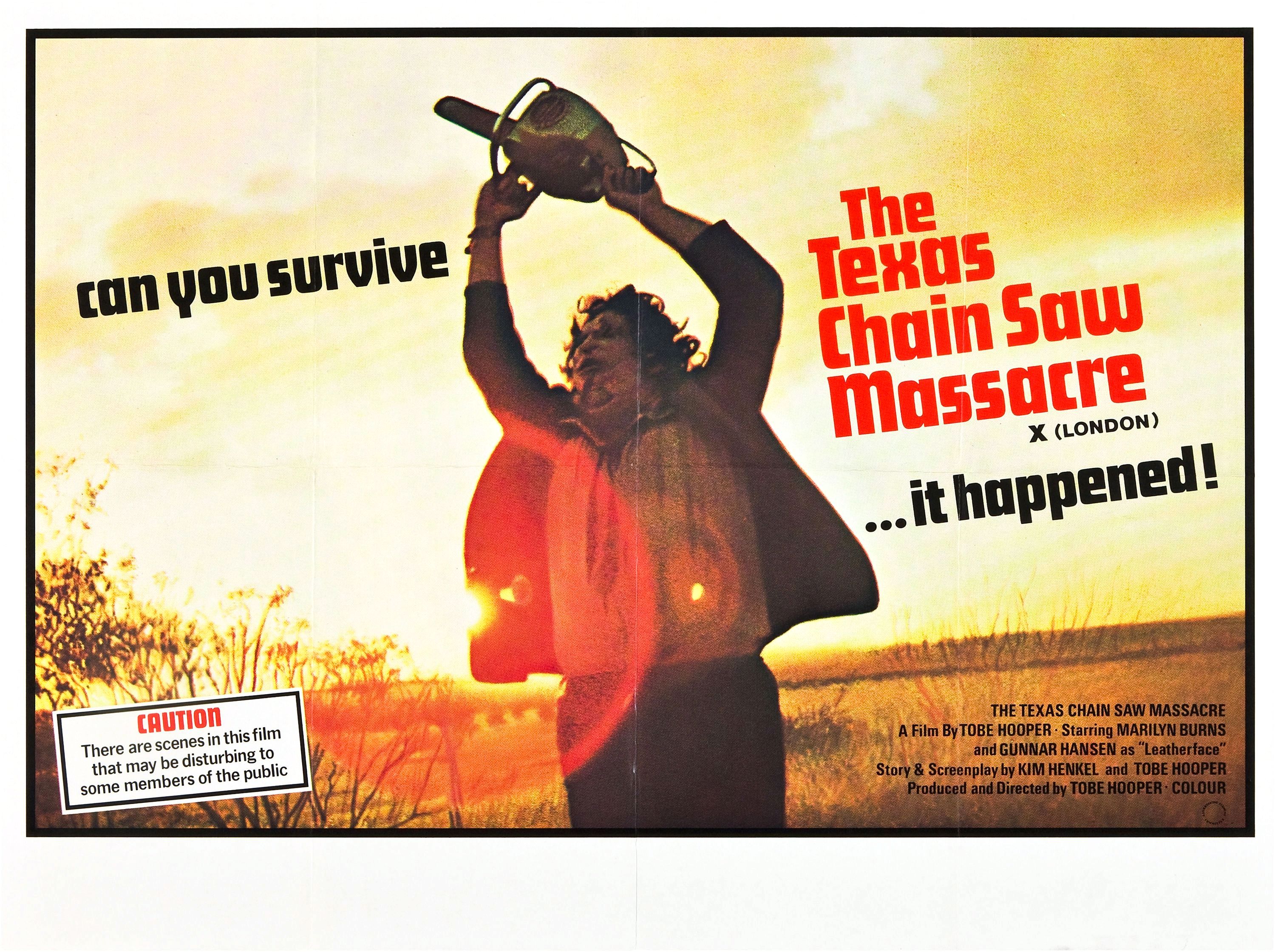

Soon after mainstream cinema-goers were bearing witness to the slick, chilling religious terror of The Exorcist, it was a low-budget film made in the searing Texas heat that would have an equally lasting impact. The Texas Chain Saw Massacre marked a seismic shift in the way horror was presented on-screen, and while its legacy of sequels and tributes is a story of diminishing returns, it remains filmdom’s most pure cinematic nightmare.

But while the film has rightfully been lauded for its carnival sideshow collection of baddies, including the razor-blade wielding hitchhiker, the wild-eyed, demented “Old Man” and – of course – the human-skin wearing, chainsaw brandishing Leatherface, when it comes to the film’s protagonists/victims, only Marilyn Burns’ Sally tends to get much of attention. For the most part, Jerry, Kirk, Pam and Franklin are relegated to being grist for the family’s mill.

Which is a shame, because the single character I most associate with Tobe Hooper’s incredible slaughterfest isn’t one of the villains, but the wheelchair-bound, endlessly put-upon Franklin, a character who is constantly abused, yet elicits almost zero sympathy.

Franklin is a fat, sweaty, irritating asshole. He’s also disabled, and his limited mobility not only contributes to his mounting frustration as the movie progresses, but it also directly leads to his own murder at the end of Leatherface’s swirling steel. Yet, despite being at a disadvantage in a scenario where he and his friends are already being victimized, his death feels like a relief to many audience members already sick of him regularly bellowing “Sally!” at the top of his lungs. We become complicit in his killing, if only for unconsciously willing it to happen.

After the John Larroquette opening narration, the series of flashbulbs, and an array of bone and corpse imagery, the film begins proper with Franklin being awkwardly lowered to the side of the road before being passed what appears to be an empty coffee can to urinate into. Startled by a passing transport truck, Franklin (and his chair) are sent tumbling down an embankment before he rolls from the chair, crying out in pain. It’s an inauspicious introduction to the character, but one that cheerfully flips the script on how such characters would normally be presented in films.

I’m certainly not suggesting that characters with obstacles should be presented unsympathetically, or even that Franklin necessarily deserves his fate. It’s clearly suggested that he’s actually been coerced into even accompanying his sister on the trip, and his mounting frustration with the heat, being regularly humiliated, and having his favorite knife stolen would make anyone a bit cranky.

But in a film where the villains are so memorable, and the violence so vicious, having a character be so thoroughly despised that his death elicits cheers is a notable accomplishment. Franklin-ish characters would appear in any number of 80s slasher films where the masked killer would inevitably be more interesting than his cookie-cutter victims, and this, in turn, seemed to influence the unfortunate tendency in late 90s horror to have all of the leads be different shades of irritating.

Nobody wants a film full of Franklins, but in The Texas Chain Saw Massacre, where the tension rarely lets up for a moment, he provides the perfect brief respite from the sheer, unblinking terror. After Leatherface finally plunges his chainsaw into Franklin’s stomach, the safety net is removed, and from that point forward the film is a delirious sprint of hallucinatory torment.

While he won’t get the awards or action figures, in his own way Franklin makes The Texas Chain Saw Massacre what it is. And for that I salute him.