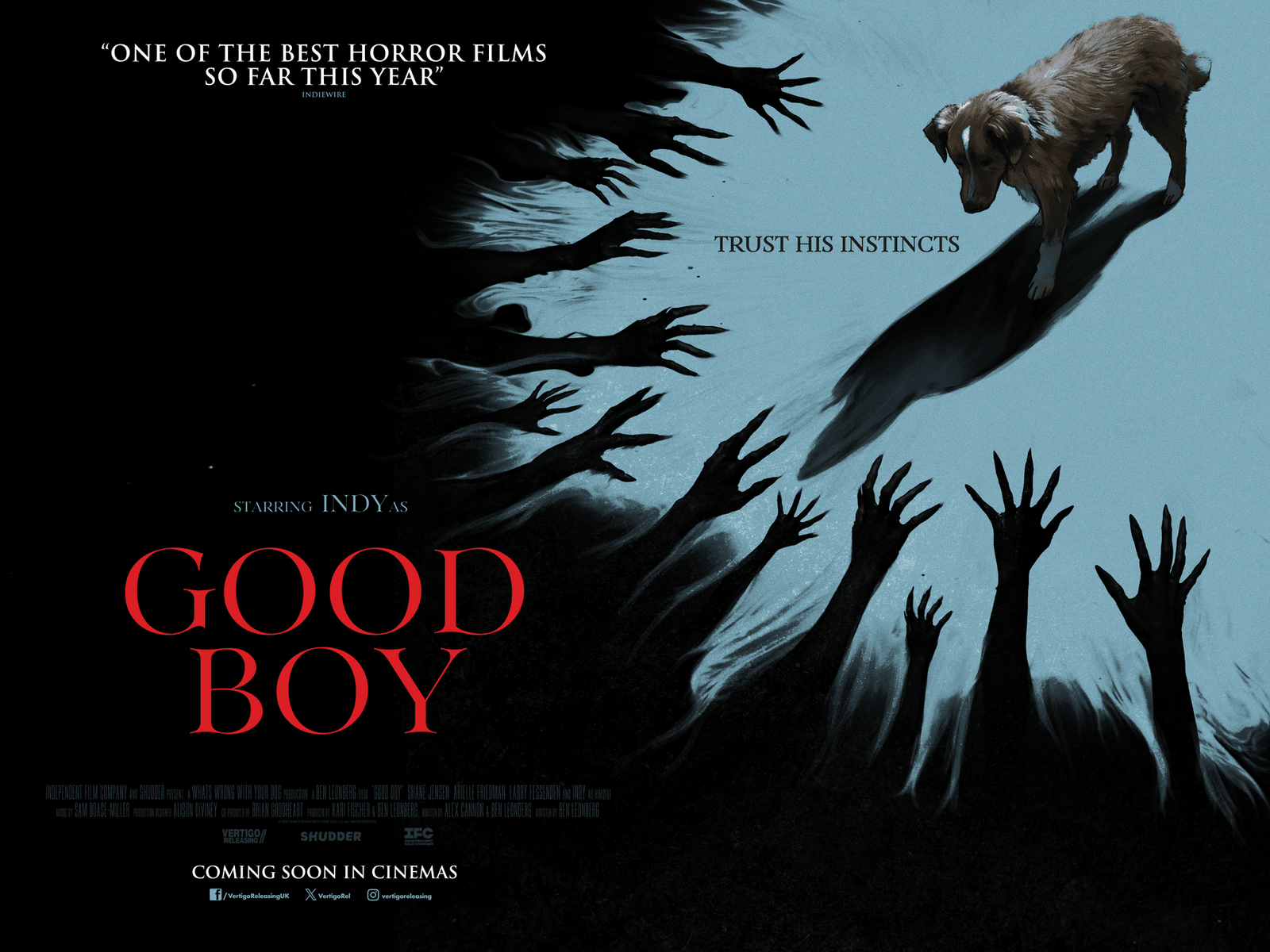

Spooky Season Kicks Off with a GOOD BOY

Good Boy takes the common experience of a dog barking at an empty corner of a home, the dog focused and locked-in onto something we as humans can’t see – and explores this phenomena as a feature length horror ride.

While at a remote family cabin together, a dog and his man experience unsettling and disquieting moments emerging from every dark corner and locked door of their space – with our furry protagonist seeing the forms and shapes of fear that his human does not.

In Good Boy, we stay tightly focused on our hero, Indy the Nova Scotia Duck Tolling Retriever. The film keeps its angles low and information sparse to capture the dogs perspective. You don’t even get clear pictures of human faces for the majority of the film – dogs don’t need them to identify anyone with all their other primary senses engaged. The film makes this a stark point by only providing faces when a dogs other sense would be of no help – when people are on screens. Exposition provided on the scentless home videos and phones offer the few faces seen in the film.

The use of a dogs sense memory as a narrative device in the film is effective – similar to the excellent Stray Dogs comic by Tony Fleecs and Trish Forstner where its furry characters rely on their sense memory to solve murders – in Good Boy this essential link between sense of smell and canine memory is depicted as a form of Psychometry – offering Indy clues and insights that wouldn’t be picked up by a human eye – depicted in startling disconnected flashes of information.

More than merely a novelty flick about a dogs point of view of the unseen, the writing in Good Boykeeps us focused on a dog’s ultimate burden: to be loved and centered in the lives of their people while never fully understanding or comprehending the complex lives of those same people. Our pets have the pieces of the puzzle without the box cover to identify the complete picture and do their best with what they have to make meaning from it.

We are placed into Indy’s world where his seemingly small stakes become essential and imposing. One of the most devastating scenes in the film is when Indy’s person leaves him alone for the day – and the normally collected and quiet Indy melts down into a loud and frenetic panic – you’re placed firmly into the dogs state of waiting and mourning while as a person you’re well aware it’s just his owner stepping out for a brief errand.

With this element of maintaining the canine point of view Good Boy fetches a fresh and unparalleled horror experience. Good Boy delivers four legged tension shaped by a sparse narrative and essential visual set pieces. The closest comparison to any recent horror films would be the incredible In a Violent Nature – the majority of the dialogue and exposition is off to the side in diagetic artifacts while the focus of each scene is on our wordless protagonist.

The most explicit information in the film is delivered to Indy in that warm sing-song voice people use with animals when they think they are alone.

The plight of working animals in Hollywood is long and twisted, with modern films increasingly opting for CGI animals when it’s clearly unethical or unsafe to feature living animal performers – you particularly see this in the modern uses of animated primates for the safety of all involved. Cats are considered a continuity managers nightmare no matter how safe it may be for them to be on set. With all of that said, dogs seem to still be singularly invested in the work of film as co-creative partners. Stories are that on safe and modern films sets dogs seem to have a blast – their happy wagging tails often being removed digitally in post production when they need to be seen as intimidating or sad for narrative purposes. Reportedly Indy the dog would continually “boop” their nose in the camera capturing Good Boy, an affection for the film and process that comes through in Indy’s performance.

The nature of filming safely and ethically with an animal and the extensive protections for them make shots of the dog in the peril of a horror flick extremely complex to capture. There is a moment in the film where Indy becomes caught in a snare trap that felt like the Psycho shower scene of filming for dogs. It felt like a hundred micro cuts edited skillfully together from of a pile of footage to make what was in reality a safe and ethical shoot with a willing dog appear as a dire and near deadly moment of terror that feels palpable.

Good Boy is atmospheric and pointed, keeping its jump scares specific and serving the narrative rather then using them as shortcuts to cover for boring stretches. Good Boy falls on the art house or elevated side of the genre for both better and worse. The film stays understated and small which serves the claustrophobia of the dogs perspective when it hits, and can drag the film out a bit when it misses. Good Boy is low-budget in all the best ways – the ingenuity, creativity and meticulous planning of the film shines through and served the best of the film where cash infusions and lavish post-production would have failed it. Outside of one janky little effects moment, this low-budget charm doesn’t break the experience.

The ending of Good Boy will be divisive – it has all the hallmarks of that sort of horror that just spirals out into theater lobbies and comment sections for years after – Good Boy will absolutely get undeserved hate for not holding your hand and letting you sit with the story and draw your own conclusions.

Creative, original, and tailor made around its central conceit of a human’s best friend experiencing our worst enemies, Good Boy successfully offers us a hound trapped in horror for the enjoyment of horror hounds.

Good Boy releases on October 3rd in the US and will be in UK cinemas beginning the 10th of October.