Now Streaming: Mickey Keating’s DARLING

[Editor’s Note: This is our second full review style post for our Stream a Little Stream column. Instead of a few short recommendations, we have one recommendation, with a full review. Jacob found this film to be far better than I did when I saw it. Perhaps I’ll write a piece on it soon to demonstrate our differing opinions, but since this is now on Netflix, you can see it for yourself.]

Writer/Director Mickey Keating crept onto my radar three-odd weeks ago with his newest, Carnage Park. I hadn’t heard of Darling, his 2015 offering, prior to Carnage Park and, honestly, after feeling pretty underwhelmed by it, Darling fell off my to-watch list. See, when your career is young, you’re supposed to get better, not worse. But Darling, which convinced me to hit play when I saw it was on Netflix AND a mere 78min in length, is a far superior film to Carnage Park.

The reference points are pretty obvious here: Repulsion-era Roman Polanski, The Silence-era Ingmar Bergman, Psycho-era Alfred Hitchcock, Last Year at Marienbad, and, to a lesser extent, Jean-Luc Godard. Using the greats as a stepping stone isn’t always a bad way to do things as Keating proves here.

Darling is a simple story of a young woman who takes a job house sitting. It’s a city row home, but the deluxe, cavernous sort that you’d really only find in the very well-to-do sections of town. It’s a house of some repute, being both old and, since this is a movie, having housed some horror in its day.

The house’s dark past is kept something of a mystery, with vague allusions to an original owner who tried to raise the devil and a whatever story of a woman jumping off the balcony just a year or two prior. But they serve as a sort of shorthand to prepare you for a haunted house movie. Throw in a creepy upside down cross necklace and murmuring voices and you know exactly what you’re getting.

So solid is Keating’s ability to play off genre conventions that it isn’t really until Darling goes off the rails that you wonder if perhaps the shorthanding of genre expectations might be a red herring. The level to which the house aura interferes with our main character’s mindset is unclear, even as the credits roll (although a mid-credits scene does answer some of it). But it doesn’t even matter: whether compelled by an ominous house presence, or sparking from some inner turmoil, watching our main character lash out is pretty intense.

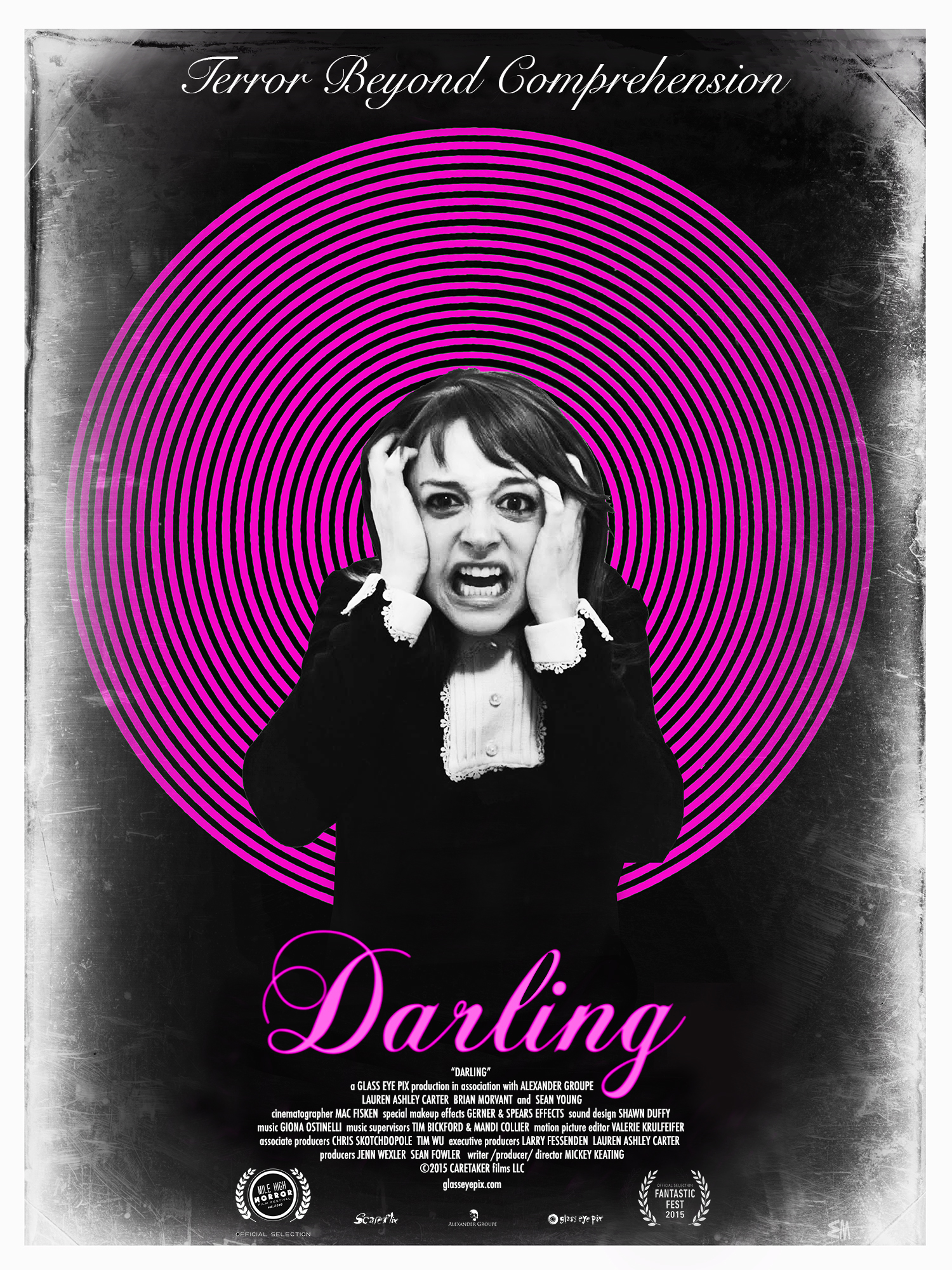

The fully black and white film is used to good effect, highlighting excellent shot composition. It aids the somber tone of actor Lauren Ashley Carter’s expressionless face as she roams hallways or jitters on immaculate sofas. It also gives Darling an early 1900s feel, even as city shots (and the cameo of an air conditioner) prove this to be a contemporary setting.

The video camera becomes a window into the main character’s mind. It blinks and spazzes out. It follows her as she roams, taking an off-centered approach to framing her. This jitteriness explains the seizure warning that is shown before Darling starts. The opening shot features a flashing background such that I was expecting Darling to go full on Enter the Void on us. But such flair is rare, and Keating prefers to communicate with an extended shot of an empty, white hallway than the blink-blink of effects.

Perhaps Darling‘s biggest accomplishment is the way it refuses to isolate the main character. These films so often feature a house in the middle of nowhere; there is no relief from the way the character is disconnected from society. Here we’re set in a city, on a normal city block. Just at the outset that gives off a different tone. Our character is never contained by the front door–she goes in and out with regularity. The scariest part is when we realize that we can’t consider her safe just because she goes outside.

Keating directs the hell out of his vision, conveying an assurance that I’d connect with a much more experienced director. The best decisions he makes is in not falling so much in love with some of his more interesting stylistic decisions that he overplays them. But his inexperience also shows at the edges of his narrative–he raises more questions than he answers, leaving some interesting ideas on the table in the process. The thin runtime is reflective of how thin the plot is; raising some of the ignored ideas would have solidified both the plot and the length. And for as rock solid as his visual aesthetic is, the facade between fiction and reality droops and we’re reminded that the main character is actually an actor and the house is a set.

Darling basically outplays these failings. Hopefully it is Darling, and not Carnage Park, that portend Keating’s directorial future.