Audio Cassette Tape, 1993.

My dad sends a package in the mail. It’s addressed to me. He’s been staying at his parents’ house, up in Hobart, Indiana for the past couple months – maybe more – getting a business off the ground. My mom, brothers and I are still living in Greenville, South Carolina at that point, waiting for the house to sell. He told me over the phone that he was sending me something about a week or two prior. I have been excitedly checking the mail every day since. I am ten years old.

There’s a package in the mail, and inside is an audio cassette.

Written on the tape label, in my father’s precise, all-caps hand writing: “JOHN BUNYAN, THE HOLY WAR CHAPTER 1.” My father has the careful, precise handwriting of an engineer. He has always been driven to pursue excellence in everything he does. He reads methodically, carefully enunciating every syllable. I don’t remember much about the text. It’s a lesser-known allegorical novel, first published in 1682, by the author of Pilgrim’s Progress. But I remember the sound of his voice coming through the speakers washed in tape hiss, wow and flutter; limitations of consumer grade, analog recording technology of late 20th century.

I listen to the sound of the air my father breathed, pushed from his lungs through vocals cords, passing through his tongue and lips, shaping words, reading aloud, recorded on audio cassette. I perceive the distance from his mouth to the microphone; the distance from the microphone to the cassette recorder; the distance of 700 miles between Hobart, Indiana and Greenville, South Carolina, all compressed into 3.81 mm strip of brown magnetic tape.

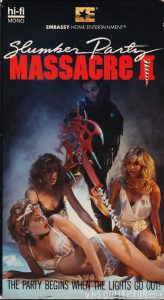

My memories of childhood have always been inextricably linked to popular culture. To movies. To music. To television. To Saturday morning cartoons. To Star Wars and ET, recorded off of broadcast television on to VHS tapes. I would dub radio broadcasts onto audio cassette; I checked out tapes from the local library. I belong to what very well may be the last generation to grow up interacting with our popular culture directly through physical media. We grew up around boomboxes, and Sony Walkmen; saw the Walkman replaced by the Discman as compact discs rose to prominence; lived through the transition of music untethering from physical object, to an incorporeal form as software data; ghosts in the circuitry of computers scattered far and wide in the ever expanding frontier of the internet. I frequented Blockbuster and Hollywood Video rental chains. I was taught to be kind and rewind. I blew into VHS players when the image on the television screen was warped and distorted, a Hail Mary, as if the breath from my lungs could fix the limitations of late 20th century consumer grade analog technology. I remember anthropomorphizing our VHS player; mistaking its technological limitations for a kind of human personality. I remember the feeling of trepidation walking down the horror aisle in a Blockbuster Video in 1992. Repulsed, but kind of turned on at the transgressions on display on the rows of clamshell cases; at flesh, and blood, and monstrous disfigurement.

And I remember audio cassettes. I remember the rattle of the spindles in the clear plastic shells. I remember the slight the feeling of resistance in the spring of the play button on the tape player; the almost inaudible sound of a static pop when the tape head made its first contact with the magnetic tape. I remember pressing my finger on the sprockets while the cassette played, and hearing the sound warp, dropping octaves as the tape slowed. I remember the feel of the tape itself between my fingers, fragile and slippery, as I pulled it out of its shell to undo a tangle. I can hear the chime in Walt Disney Read-Along cassette tapes. The narrator saying:

You can read along with me in your book. You will know it’s time to turn the page when you hear the chimes ring like this.

The memory of the tape became a thing in itself.

I remember how my dad marveled at the crisp clarity of compact discs. Driven by the pursuit of excellence, he loved their increased clarity and dynamic range. “It sounds real” he would say, “like it’s in the room.” It wasn’t long before they completely supplanted cassettes in our home. While I have no memory of a turntable in my childhood home, I remember the absence of nostalgia in his voice when my dad spoke of records. When he embraced a new audio technology, he never looked back. But I remember reading the disclaimer on compact discs in the early 90s:

The music on this compact disc was originally recorded on analog equipment. We have attempted to preserve, as closely as possible, the sound of the original recording. Because of its high resolution, however, the Compact Disc can reveal limitations of the source tape.

And my mind drifts to the image of a piano in a sandbox. Something I had read once; Brian Wilson, barefoot, to feel the sand between his toes, composing “Surf’s Up” in 1966. Brian Wilson pushing his band, the Beach Boys, further than anyone had ever gone in American Popular music. Brian Wilson, who had never surfed in his life. Brian Wilson, deaf in one ear, unable to perceive the effect of hi-fidelity, stereo sound. Brian Wilson, better than the Beatles. Brian Wilson, wide-eyed, stretching out to pluck those elegant chords that hung in his mind like heaven from a thread. Brian Wilson, composing teenage pocket symphonies to God.

Teenage pocket symphonies to God, dubbed on ½” reel-to-reel magnetic tape. Piano chords and voice washed in the faint sound of tape hiss.

And I’m reminded of another piece of 1966; American composer Steve Reich debuts “Come Out”, a piece of process music created by tape loops. Reich found compositional potential in the misfiring of imprecise machines. The piece is built around the recorded voice of Daniel Hamm, 19 years old in 1964, a falsely accused member of the Harlem Six, arrested for a murder he didn’t commit. He spoke into a microphone in an interview: “I like, open the bruise up to let some of the bruise blood come out to show them.” Once caught on tape, it ceased to be Daniel Hamm, and became a thing in itself; an instrument; the sound of his voice; air pushing out of his lungs, through his wind pipe, through his vocal cords, his tongue and lips forming the shape of syllables, strung into language; recorded onto magnetic tape.

Come out to show them. Come out to show them.

Reich redubs those five words on two channels. Two tapes looping continuously; slipping out of sync due to the limitations of mid-twentieth century tape recording machines; limitations which Reich exploits masterfully. Two voices in unison begin phase shifting, mutating and reverberating. Two voices become four. The spoken words becomes indecipherable, the sound of a voice shedding the imposed signifying meaning of language, becoming pure sound. New rhythms and textures are teased to the surface. Four voices become eight. Eight voices become 16. And on and on. An impenetrable wall of sound, rattling, and washing like waves over the listener, until the physical tape itself decays, and the chorus of voices fades into the oblivion.

And I remember another tape. I am two years old. My father is sitting cross-legged on the hardwood floors of the first house I lived in, on Lawndale, Hammond, Indiana, 1984. I recall the light yellow paint on the exterior of the house. I recall the grand piano that stood in the corner of the living room, inherited from my maternal grandmother, who died 2 months before I was born. We are playing with a tape recorder. “How about I interview you?” my dad asks. His voice is warm and slightly higher on the tape; there is the slightly reedy intonation, a trait that my father shares with many of the men in my family family. I share that trait too. I am two years old. I live on Lawndale. I excitedly exclaim I live in Hammond Indiana, the words pouring out of my mouth in a tangle of syllables. “Slow down,” Dad urges me again and again, trying to get the perfect take. “Don’t push that button. Don’t push that button.”

But I wanted to push that button. I wanted to push every button. I always have, and I still do. To see the REC light engaged. To watch the UV needle jerk at the intonations of my voice, to play it back to get the uncanny sensation of encountering your voice as someone else does.

Do I really sound like that?

Dad always acted a little sheepish when we would replay that tape; my brothers and I. And we played that tape a lot. I loved listening to it, and would replay it over and over, until one day it mysteriously disappeared. I’ve always suspected foul play, but Mom and Dad have never admitted to it. I think they’re hiding something.

But the memory of the tape became a thing in itself. Sounds of my father and me, and in the background, the voice of my mother, and cries of my newborn brother Jake. The sounds are not us anymore, but the sound vibrations our voices made on an evening in 1984, caught on magnetic tape. We documented ourselves. We spoke our names into microphones, and wrote them onto audiocassettes. We grew older; our bodies changed and matured; skin cells died and were replaced with new cells. The timbre of our voices change with age. The memories themselves warp and are rearranged by the limitations of our own physical brain matter and subjective mind’s eye. The fingers that turn over an audio cassette tape today are not the same fingers that pushed play all those years ago.

But the tactile memories remain.