ISOYC Issue #3: Why Would You Call This Film HAPPINESS

If you’re new to this column, we’d like to offer an introduction of sorts…

Here at The Farsighted, we aspire to highlight independent and experimental filmmakers to provide exposure to works that are often unseen or misunderstood by common movie goers. No genre would best exemplify these two elements better than that of the transgressive film. In this essay series we will be delving into extremity to highlight the artistic merits that are so often missed by those unfamiliar with the sub-genre. For those unfamiliar with transgressive cinema, this will be the perfect introduction as we will explore what brings these titles into the lexicon of cinema. But don’t worry initiated delinquents, those who have already perused French Extremism, consider Salo or The 120 Days Of Sodom a religious experience, or hold your tongue whenever someone asks “What should I watch?”I Spit on Your Cinema looks to not just provide exposure for these often misunderstood films, but to encourage further exploration into the piece’s morbid heart.

With the transgressive film genre often being one drenched in macabre and tragedy, one can’t help but wonder if there is ever a time to laugh within its sharp lens. Comedy has made a long time game of confronting its audience. More controversial than the dare to look into the unmentionable or taboo has been the ability to laugh at it. But to do both and put it on a screen? Some would consider it an absolute travesty, others a feat of cunning craft.

In the 60s, the godfather of modern film – Stanley Kubrick – made an incredible dare to turn Vladmir Nybukov’s infamous novel Lolita into a comedy starring acting legends Peter Sellers, James Mason and Shelly Winters. It was given an X rating and met with severe scrutiny from censors. Though the age of Lolita’s character was changed from nine to twelve and the frame displayed no depictions of sexuality between her and the tormented deviant Humbert Humbert, the subject matter alone earned the film its black mark. To take on the topic of pedophilia and dare its audiences to laugh at it was something that had gone unheard of in the cinematic landscape.

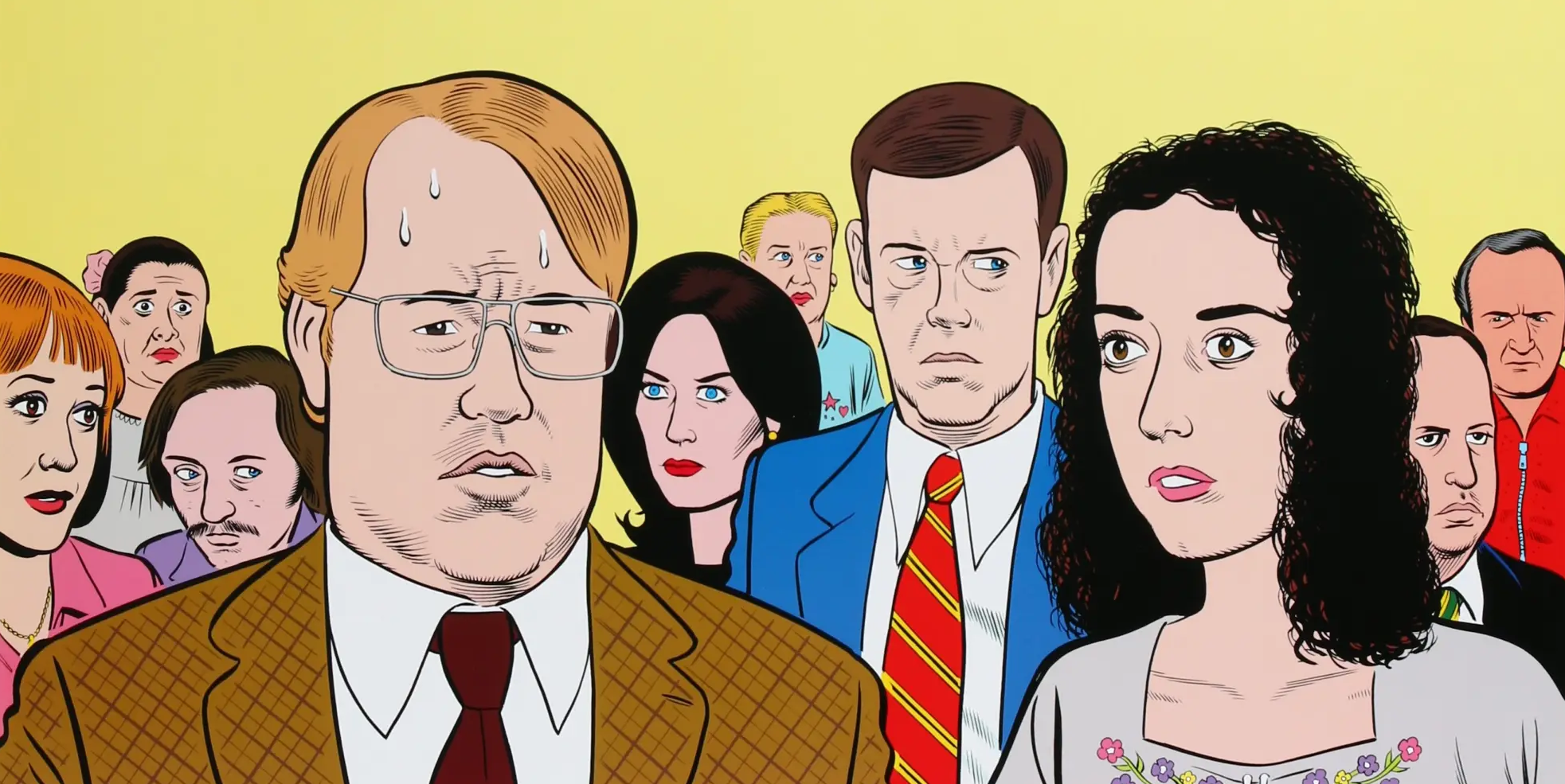

A New Jersey filmmaker, Todd Solondz would later take up this mantle and once again challenge audiences to chuckle at the foul face of human condition with Happiness (1998) starring famed actors such as Jon Lovitz (SNL) and Phillip Seymour Hoffman (Boogie Nights, Big Lebowski). With other notable actors such as Cynthia Stevenson, Dylan Baker and Jane Adams who’d made many television appearances, Solondz crafted a signature palette of bright colors and rancid punch lines into a tongue-in-cheek tone that all but tells you to choke on it.

After receiving an NC-17 rating from the MPAA, the film was released Unrated to avoid cuts. Sundance refused its entry due to the content despite a rave review from Roger Ebert’s Top 10 Films of 1998 and to this day it’s challenging to find it available on any streaming service let alone a rare physical copy. Still, the film lives on in underground film circles as an absolute classic and tour de force in what it means to make an art of transgression.

As the title suggests, Happiness is a film with a theme that concerns us all. Our lives, according to many philosophers throughout the ages, are primarily dictated by this pursuit. Everyone has an ideal they hope to achieve. A stage at which they will finally say they are happy. But as anyone will tell you, happiness is an illusive thing. It comes in and out of our lives as a visitation rather than settling and spurns us to give it chase. To try as hard as we can to somehow woo it back into our lives.

Solondz crafts a very striking meditation on this word and its consequences with his tale of a family. On the surface they reflect the suburban ideals. Wealth, family and social status fulfill the mainstream standards of a virtuous life. However, deep within lies evermore urges that make these achievements feel trite. Dr. Maplewood (Dylan Baker) struggles with his secret longings for the underaged, his wife Trish (Cynthia Stevenson) struggles with the question of being more than a housewife and their son Timmy (Justin Elvin) confronts puberty and the desire to ejaculate. Problems their money and status could never solve.

Compounding the nuclear family’s concerns are those of Trish’s two sisters. Joy (Jane Adams) with her struggles to find identity and success as an artist alongside the calloused musings of fame from achieved novelist Helen (Lara Flynn Boyl). As their parents undergo divorce in their twilight years and a harassing pervert Allen (Phillip Seymour Hoffman) intrudes into their lives, a compelling canvas spatters a spectrum of lives both within and beyond societal or moral standard. The courtesy extended by Solondz to the amoral wants and desires of his characters can make this film quite a challenge for viewers but holds a compelling question of its subject.

Joy is introduced in the first scene on a lovely romantic dinner where velvet surrounds and a tuxedoed suitor Andy (Jon Lovitz) sits across from her. Joy’s revelation that this is not a celebration of love but a voluntary departure sparks an incredible outcry from Andy who declares “I’m champagne baby. You’re shit and you’ll always be shit.” With Joy’s heart shattered she seeks refuge at Trish’s home where Trish gives some misguided comfort in the fact she’s always been sure that Joy would never amount to much. Joy admits that Trish does seem to have it all but at least she still has her career as a musician. To which, Trish offers a polite smile and tends to her rampaging children who threaten death and violence armed with plastic weapons.

Departing from the pallatable desires of love and success, Dr. Maplewood is introduced as a detached apathetic therapist who listens to Allen fawn over the desires of his neighbor and the awareness of his bland nature. Rather than be attentive, Dr. Maplewood plans his trip to the store on the way home including milk, eggs and a teen boys magazine. In the parking lot behind the store he indulges his perversion, tucked away in the backseat he achieves his climax as a young mother and boy walk unknowingly by. In his own session with a therapist he confesses that the true tragedy of his dreams where he massacres a park of lovers and families with an assault rifle is that he doesn’t die in the end.

The sociopathic therapist returns home to his suburban ideal and entertains Trish’s desires for gossip. She laments the perfect life she has and the comparison to Joy and Helen’s lives give her a sense of superiority. Knowingly a wolf among the sheep, Dr. Maplewood smiles and plays his role as husband and father to perfection. Though when his son Timmy approaches him with a concern about being excluded amongst his peers for not having successfully masturbated yet, Dr. Maplewood’s fangs begin to show.

Desperation sweats in illustration of the struggles with desire on Allen’s fingers as he dials phone numbers from the phonebook to declare his desire to fuck and pins postcards to his wall with semen. However when he dials the number of his neighboring crush, his unhinged desire is suddenly clamped. Helen shrugs off the curious hang up call from Allen’s panting breath and returns to her life of artistic leisures and achievement. The lists, the fame and the beautiful man in her bed offer their indulgences but Helen’s dry tone and all black visage remark them with apathy. The phone again rings and Trish informs her that their parents are getting divorced, Joy is lost in the world and they should have dinner.

In conversation with Helen, dining at the very scene of Joy’s devastating restaurant experience, the two sit and ponder how they have it all. Trish and her family, Helen with her career, it’s gotten Trish to wonder. What if, like Helen, she were to write a book? A confession of dissatisfaction from her portrait life. Helen patronizes and says she should but warns that all the fame, the sex, the success… it still doesn’t satisfy her and she doesn’t know why. Trish agrees, maybe she shouldn’t try writing, after all her life is busy and she really wouldn’t want all that success. Helen all but spits her drink out at the delusional audacity of the statement.

As the film progresses the constant torment of desires plays out into each of the character’s lives. Dr. Maplethorp finds himself in lost psychotic yearnings when Timmy brings his new friend Johnny over for sleep overs. At baseball games his gaze becomes more and more apparent, he plots to poison and rape Johnny in his living room, his conversations with Timmy about ejaculation become more escalating dares against innocence. Trish remains oblivious to her husband’s perversion while Joy abandons her job to do work as a strike breaker at a language school for immigrants and Helen begins to entertain Allen’s lusting phonecalls in hopes of feeling something again.

Soldondz portrays happiness as state of indulgence and risk. From being as simple or innocent as young Timmy’s desire to experience his first orgasm to Dr. Maplewood’s heinous infatuations, each character’s struggle is met with a gleeful nihilism. Throughout the film every attempt to find happiness becomes a dangerous dissatisfaction. The further characters pursue their desires, the more incapable they seem of it.

Scenes froth with a gleeful palette of color tones that coat the back drop of the affluent 90s. Music punctuates with giddy classical music and an upbeat melody from Joy’s guitar becomes the film’s theme. Following the comedic aims of subversion and absurdity, the words of characters betray with their dry tones. Joy’s lyrics sing of distress and ask why happiness will never find her, Helen’s famous book is titled Pornographic Childhood with stories titled “Rape I”, “Rape II”, “Rape III” and so on when she herself has never had such experiences. Trish’s picture perfect family is haunted by the pedophilia of Dr. Maplewood and no matter what Timmy does he still can’t get his body to operate.

It’s in the escalating absurdity of the character actions that the comedic tones make themselves apparent. Every action is met with a struggle which perplexes characters in their pursuits. While Dr. Maplewood’s poisoning attempt of Johnny is indeed a horrific deed, the desperation of Dr. Maplewood becomes laughable when thwarted by a young boys simple distaste for ice cream. In front of his family, Dr. Maplewood sputters and flails, offering to get Johnny whatever he wants; any fruit juice, any dessert, any sandwich, anything he can slip his discrete sleeping powder into. Even if he has to go find a store that’s open past nine.

Though Johnny’s demand for a tuna sandwich is met with a completion of Dr. Maplewood’s sinister act, the frustration and desperations of the character are farcical. In other instances Joy’s innocent heart crosses a picket line for union labor and is unwelcomed by students despite her good intentions. Helen entertains Allan’s harassing calls in search of some connection to abuse only to become a bitter romance when the two finally meet in person. Their fantasies shatter at the moment of actualization. The divorced parents struggle with being alone with their freedoms, finding it useless.

With every attempt at achieving happiness, each is met with a discouraging reality. Dr. Maplewood’s pursuits lead to discovery and criminal charges which explodes the nuclear family. In the aftermath, Trish and kids become homeless. Timmy’s faced with further admonishment by his classmates. Joy is abandoned by a thieving and married lover which costs her her job and leaves her with only her guitar. Helen’s inspirations fall victim to fallacy and leaves her no closer to writing her next book.

The film ends with the family members, sans the incarcerated Dr. Maplewood, sitting across from the divorced elders. Each comments no further progress on reinstating their life ambitions or successes but agrees it’s nice to be sitting as a family again. To find some resolve they offer a toast. “To Happiness.” Alcohol washes down in silent pity only to be shaken by the sudden cry of triumphant glee from the back porch where Timmy declares “I came!” with a smile of pure satisfaction in front of the wallowing adults.

Behind the satirical jabs and black humor is a very introspective look at the nature of happiness. What makes Solondz’s work not just a piece of shock and awe is its ability to marry both nihilistic realities with a laughing acceptance of it’s truth. He portrays happiness as destructive and fulfilling. It’s illusive nature sparks a universal yearning that consumes us for better and worse.

Intentionally antagonizing with its offer of empathy for heinous desires, Solondz’s decision to do so offers a more robust understanding. Any story is hinged on a character’s wants just as all of our lives are dictated by our pursuits for happiness. For the most part this is what makes us feel good and because of this we view ourselves to live good lives. We feel just in our decisions as Trish does. But as Solondz shows through Dr. Maplewood’s incurable ailment, it is also a fatal thing that curses us to do what we shouldn’t. Yet its promise is so desirable we may risk everything and lose it entirely. In the case of Joy it may even leave us as a rare and abusive stranger who could not possibly return our devotion to it.

As uncomfortable as these ideas are, this is why Solondz invites us to laugh at the pain that haunts us all. Because in the end that’s all we can do, we can choose how to react. Utilizing the subjective nature of comedy Solondz gives you the choice to stare into the despair with a chuckle or become outraged with your head plumped back into Hollywood endings neatly wrapped with illusions of grandeur.

Much of transgressive cinema’s aims appear to be that of depicting the nature of human realities with its most sinister and vile flaws present in its examination. It dares to understand the shadows in our souls and how it balances with the light. Remembering that there is light can often be daunting when faced with notable transgressive titles such as Henry: Portrait Of A Serial Killer, Anti-Christ, Salo: 120 Days Of Sodom, or Martyrs. Yet, films like Happiness, Man Bites Dog, Lolita, or Pink Flamingos have found a way to subvert the subversive genre with playful tones that still echo the explorations of the less approved or vile heart of mankind.

Happiness defined Todd Solondz’s career and he has gone on to become an auteur figure in satire cinema with cult hits Welcome To The Doll House (1995), Life During War Time (2009) and Wiener Dog (2016) still finding their audiences and turning the heads of the unexpected. True story, I went and saw Wiener Dog at a matinee where an older couple had mistaken the film for a cutesy pet-drama only to ask themselves at the end “What the hell was that?”. He had changed their lives forever that day, for years they would go on to tell their friends of this awful film they saw where a dog accompanied four souls into tragedy. Even worse they had actually laughed at some parts of it. In that moment I shared the smile of Solondz and revelled in his triumph.

While Todd Solondz’s artistic merits have been certainly earned by his colorful lens and distinguishing set pieces. Behind his camera has always been the cunning words that skewer and jab with perfected abandon to split your sides and laugh at the terrible truths wherever they may find you. Happiness marked itself as a bold and ambitious piece that drew a great amount of scrutiny, but what has always held it up like many other great works of transgressive cinema is Solondz ability to craft story. With its bleak blends of humor and existential drama they dare you not to laugh. As H.P Lovecraft once commented “The world is indeed comic, but the joke is on mankind.”

With films like Happiness we are invited into the admission that life is at times not just tragic but absurd. That within ourselves we possess similar fates of futility and should choose not to feel sorry but laugh at it. That we too can be in on the cosmic joke if we so choose to accept the invitation offered.