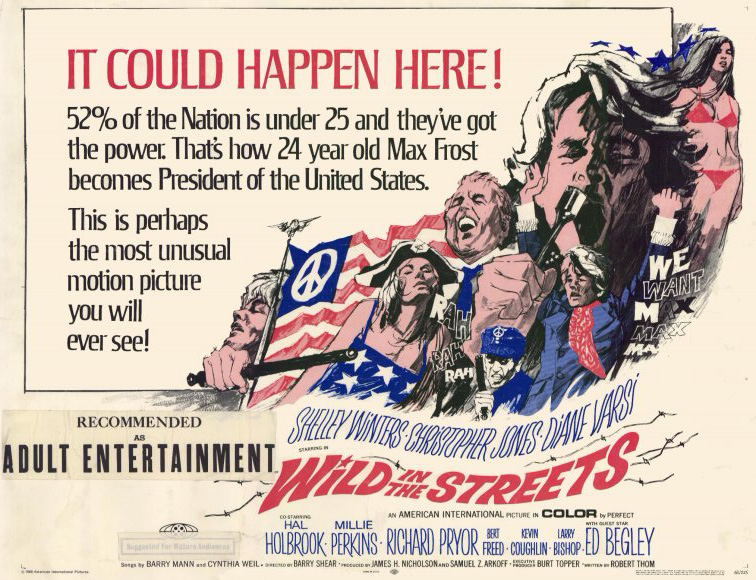

Things That Make You Go “Huh”: WILD IN THE STREETS

My reaction as the ending credits began to roll on Wild in the Streets was something like, “Huh.” Ninety-seven minutes of film had passed by my eyes, building up some really interesting ideas, some unique characters, and some oddly still-relevant political satire, only to turn the whole movie into an awkward punchline. “Huh,” pretty much summed it up.

What “Huh” doesn’t quite cover is the 96 minutes prior to that last one. Wild in the Streets is a weird, weird film. A pleasant sort of weird, mind, but weird nonetheless.

It kicks off with an awkward series of segments from the childhood of main character, Max Frost (Christopher Jones). These segments are shocking to 2016 eyes for their crass mixture of child abuse and comedic timing. With his mother, Mrs. Flatow (Shelley Winters), howling about how if she has a boy, she’ll just die, only to follow that scene up with an “It’s a boy!” announcement card. The imagine of baby Max crying in his crib while we hear Mrs. Flatow arguing with his dad, Mr. Max Flatow, Sr. (Bert Freed), telling him that she’s going to raise Max to know what men are like, the terrors they cause, and et cetera, all while the camera gets closer and closer on Max’s tear-streaked face. Mrs. Flatow shrieking “It’s dirty, dirty, dirty!” when she catches kid-Max kissing a friend on the cheek. “Dirty little girl! Dirty little boy!”

Shot as a straight drama the scenes would be disturbing, but the timing suggests the scenes are intended to make us laugh, thus making them that much more cruel. In between each of these scenes the screen freezes and goes dark, as marching band-style patriotic music blasts for a few seconds, followed by the next scene. It’s so utterly baffling that someone would look at these little scenarios, which only account for a total of five minutes of film, and think, “Let’s make this hilarious.”

And I love it. Those opening scenes are some of the best within Wild in the Streets. Oh, they’re shocking and terrible, and by rights no one should support such attitudes, but I’ve never seen anything quite like them. It’s original and audacious and, however horrible to modern eyes, endearing. They’re also key to Wild in the Street’s ongoing theme of conflict between Max and his mother.

The most fascinating scenes within Wild in the Streets give us adult Max interacting with the mother he despises. His position, as the opening set of scenes showcases, is simple: she’s a terrible person that he’d rather not have anything to do with. In fact, he seems to waste very little time thinking about her. She is a clogged toilet that he occasionally has to plunge out of his life. Just like you don’t think about a clogged toilet until it happens, he doesn’t think about the woman who didn’t want him.

It’s through the lens of this indifference that Mrs. Flatow becomes a compelling (though not sympathetic) character. She’s blind to her faults, willing to let bygones be bygones without comprehending that she’s not the wronged party in this tango. But as her son becomes a household name, she becomes an avid fan, certain that she’ll be remembered and exalted to his level sooner or later.

I feel like I could go on all day about how fascinating Mrs. Flatow is, and she’s not even the central figure within Wild in the Streets. In fact, the larger storyline doesn’t even require her presence within the narrative.

Max, leader of an emerging rock and roll band, is seeing a quick ascension into stardom, packing out theaters and getting aired on TV. He agrees to play a political rally for Senator candidate Johnny Fergus (Hal Holbrook), who is running on the platform of lowering the voting age to 18, despite a lack of interest in Fergus himself. At as his band performs, Max applauds lowering the voting age, but mentions that at 18 his 15-year-old guitar player, Billy Cage (Kevin Coughlin), is still incapable of voting.

This sparks a political revolution spearheaded by Max and his bandmates as they rally the youth into mass demonstrations, demanding that their voices be heard. The old, traditional politicians, threatened by these uprisings, quickly grant the youth their vote.

The first half of Wild in the Streets charts Max’s rise as both a voice for a generation and as a game changing politician. His policies of handing power to the youth gives him a swell of support from the people that make him an unstoppable force–and when the system does manage to stop him, his lack of scruples allows him to easily dodge. The second half, then, illuminates the extent of Max’s anti-aging agenda and plays it out to an oddly satisfying, but logical, outcome (albeit one blemished by the ending punchline).

Of course all of this political nonsense is infused with an awkward comedic tone. The subject matter isn’t really strong enough to stand alone as a drama, so it has to be comedic. But it’s off-kilter, giving Wild in the Streets an imbalanced narrative flow. Some of this boils down to the fact that there isn’t actually a plot here–you can hobble together a narrative around the skeletal core of “single issue rock and roller doesn’t see logical implication of policy,” but it’s not a plot in any real sense. Instead we get a whole lot of slice-of-life scenes strung together; they act as blobs of story on the impressionist’s canvas. A dab here, a dab there, and finally we get a big picture.

There’s a wistfulness to Wild in the Streets that makes Max’s political rise and vision endearing. Even though few of us would argue that certain ages should be legally barred from the workplace (at least, based on age and not ability) the film’s portrayal of the old boy’s club that political lifers embody is searing. At the same time, so hard is the turn to show off the absurdity of such a platform that it upsets any point that preceded. By the end it’s hard to tell if the movie is a subversive criticism against the proverbial Man, an even subversive-ier criticism against youth culture, or completely devoid of criticism and is just a bunch of scenes to say, “LOL what if a rock star took over politics.”

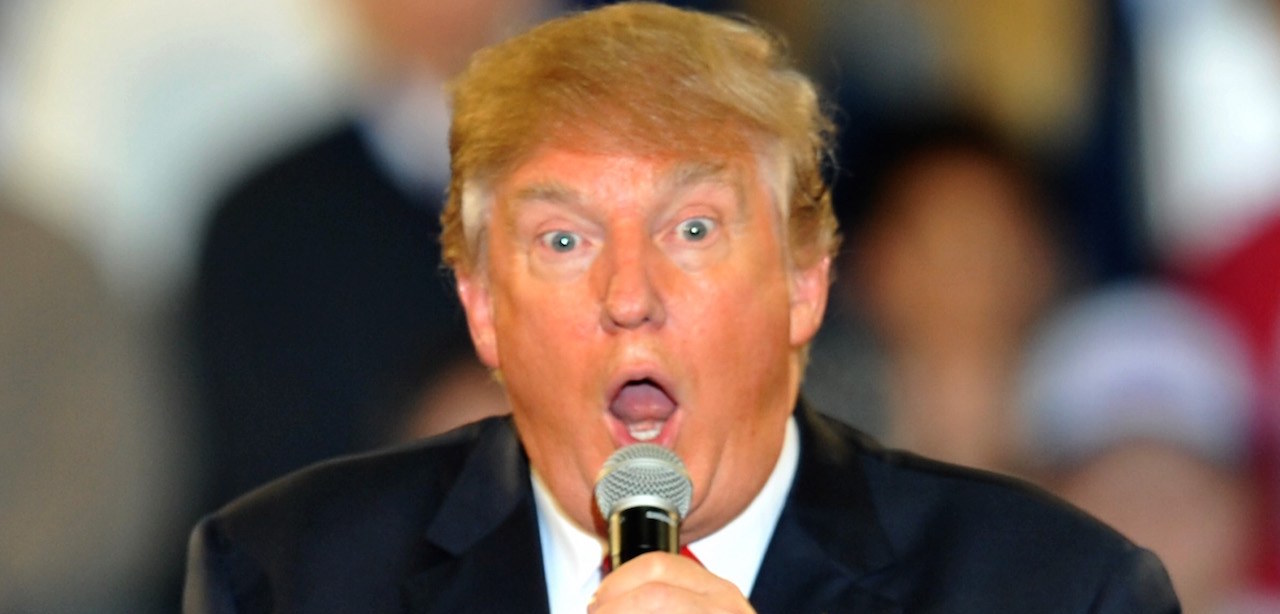

In a year where Donald Trump is an actual presidential nominee, this mixture of celebrity and politics and othering feels uncomfortably prescient. Even though the issue Max runs on and the issues Trump is running on are different, they both tap into a similar dissatisfaction with the political status quo. And maybe that’s the rather brilliant thing about watching Wild in the Streets in 2016: it shows the appeal of an outsider to the system, while also showing the danger that an outsider poses. I don’t know how well Wild in the Streets would play in a different political season, but for right now its strengths outweigh the weaknesses inherent to the narrative. Olive Films, who just released this on Blu-Ray and DVD, have a good sense of timing.