31 Days, Day 21: Dr. Caligari’s Neighborhood

[Editor’s Note: This column began this month but will continue in some form after our 31 Days celebration is over, though the exacts are be ironed out. Essentially, this is where we take a movie on Netflix, watch it, and argue or agree about what we think. I kinda stole the idea from Cinapse’s Two Cents column, which is one you should definitely check out. But before you head over there, real below.]

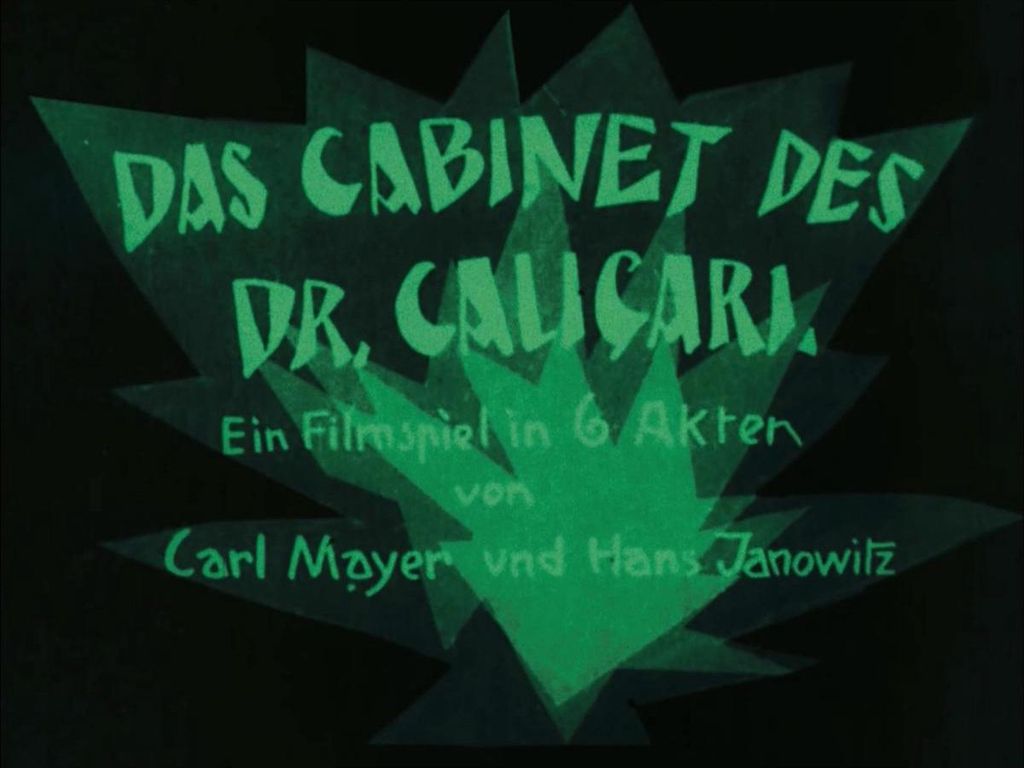

As a newly minted “horrorhound”, The Cabinet of Dr. Caligari seemed like the most essential of homework amongst a list that otherwise consists of 12-movie slasher franchises, a handful of John Carpenter films, and a few torture-porn movies people have somehow convinced me I need to see. And sure enough, Caligari did not disappoint.

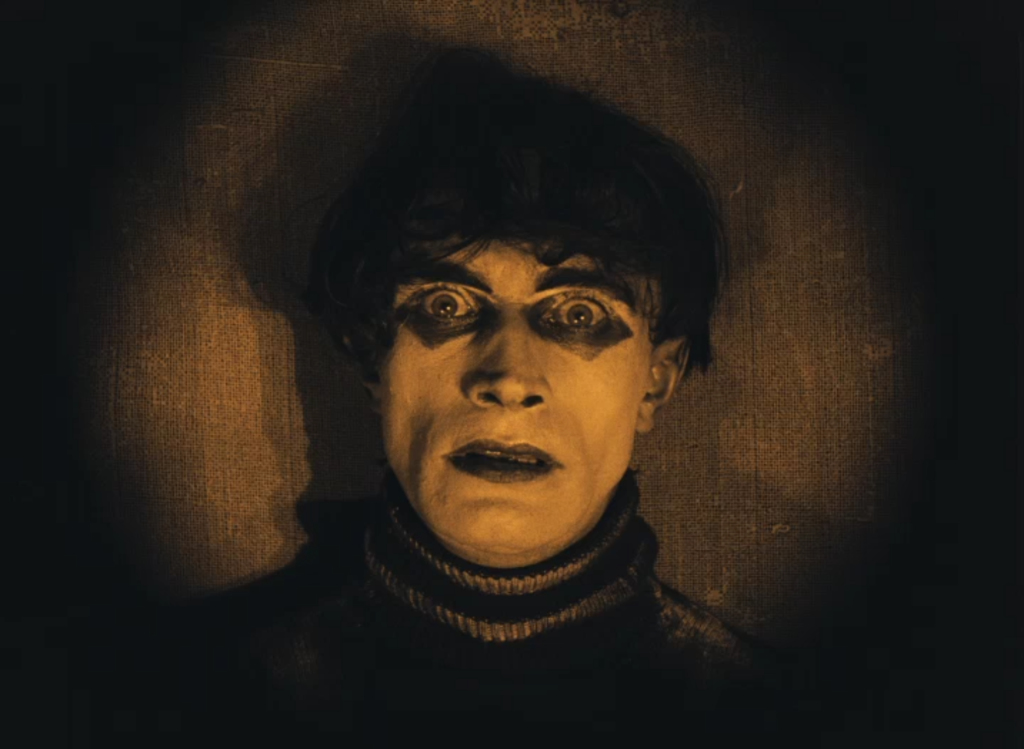

Serving as a both a fascinating piece of cinema history and a template on which many a twisty horror narrative would be built, The Cabinet of Dr. Caligari more than earns its seat amongst the great classics of the genre. But I was ultimately more intrigued by it as an early film than I was by its merits as a horror movie. The influence of theater on early cinema is very apparent – the camera is exclusively static and editing is minimal and often accompanied by full blackouts between scenes, as if opening and closing a curtain for a set change. The sets themselves are all dramatically designed to express the mood of the various settings – mostly sharp, obtuse angles in the city to illustrate how oppressive that space is, contrasted only by the rounded edges and corners of Jane’s quarters. Every close-up of an actor is accompanied by a tightening of the frame so that it’s a full blackout on screen except for the actor’s face, as if a spotlight is being used. It’s so interesting to see the beginnings of film as a visual storytelling medium, when theater was the only frame of reference for how to do such a thing. There was so much yet to be learned, especially about editing – but that’s exactly what made it such an engrossing watch for me.

Every choice that was made was riveting. Anytime it cut from a wide shot of two characters talking to a close-up of one of them, emphasizing their expressions, it was thrilling. I realized that, without sound, without dialogue, there’s nothing to carry me as a viewer from that shot of both characters to the close-up of one if I don’t yet have that cinematic language to base that sequence of shots on. It’s the careful placement of dialogue and title cards along the way that make those storytelling beats clear. But the movie never goes overboard with the use of cards – I was truly impressed by how much information is conveyed visually, and how the movie teaches you to watch it by slowly increasing the pace of edits, also mimicking the increasing madness of Francis. There’s also this interesting “tinting” effect used to convey different kinds of light, like day and night, indoors and out, and seems like a truly “special effect” for its time. The version of this that’s on Netflix has a great score too – though I’m unable to source which version it is exactly, I believe this is from one of the Kino Lorber editions, specifically the original orchestral score composed by the Freiburg Conservatory of Music in Germany.

Finally seeing what Roger Ebert famously called “the first true horror film” was a real treat, though for entirely different reasons than I expected. As a horror movie I’d say it’s oddly as good as it is dated. This has inspired and influenced so much I’d be surprised if you couldn’t see where this was going right away which takes some of the tension out of it, but it’s a truly dark and nasty film with some really incredible art direction that I ultimately really enjoyed watching. I would gladly watch this again, not only to unpack some of the thematic work about subservience that is clearly running just under the surface, but especially since there are so many different scores that have been released for it – great reason to give this a re-watch every few Octobers.

JACOB GEHMAN: Can we talk about chairs? I know, I know, an hour and seventeen minutes of one of the most important German expressionist films and my takeaway is the functional things we sit on. Yet, throughout the film, there are moments where I stopped thinking about The Cabinet of Dr. Caligari and, instead, started thinking about chairs.

JACOB GEHMAN: Can we talk about chairs? I know, I know, an hour and seventeen minutes of one of the most important German expressionist films and my takeaway is the functional things we sit on. Yet, throughout the film, there are moments where I stopped thinking about The Cabinet of Dr. Caligari and, instead, started thinking about chairs.

For example: One of the early scenes in which we see a normal living room (well, “normal” by German expressionist standards). In this room are two chairs, completely ignored by any characters on the screen, two utterly standard chairs. Except these chairs have backs that are two, maybe three times taller than a normal chair back. It’s like see a mini ladder just sitting in the middle of the room, and I started to wonder if such a tall, absurd, chair was normal in Germany in the 1920s, or if it was just another weird visual element in a weird visual film.

As great as those chairs are, we see the exact opposite later on: tall, pedestal-type seats without any kind of back that perch the sitter far above the ground, forcing him to lean into his desk to do his paperwork. These are most obviously seen in the police station, where officers spend time looking busy until an actual case befalls them. They look quite painful to sit on, and tall enough that a failure to keep sitting would result in quite a tumble.

Some viewers may find Dr. Caligari to be quite horrifying, others Cesare, and even others the insane asylum or fair or the casket in which Cesare spends most of his time. But, let me assure you, it’s the chairs that are most befuddling in this world.

LUKE TIPTON: With faces caked in thick, garish makeup, the screen cut up by severe, jagged angles and cartoonish sets that distort space and perspective, The Cabinet of Dr. Caligari is a cramped, disorienting fever dream that looks like it’s about to collapse in on itself at any moment. This is one of the cornerstones of horror cinema, and you can see its direct influence on everything from Carnival of Souls to Tim Burton to The Babadook.

LUKE TIPTON: With faces caked in thick, garish makeup, the screen cut up by severe, jagged angles and cartoonish sets that distort space and perspective, The Cabinet of Dr. Caligari is a cramped, disorienting fever dream that looks like it’s about to collapse in on itself at any moment. This is one of the cornerstones of horror cinema, and you can see its direct influence on everything from Carnival of Souls to Tim Burton to The Babadook.

The exaggerated performance style of the actors here is a bit of a hurdle for me. It’s theatrical to the point of being ridiculous. And given that it’s just shy of a hundred years old, it takes some work finding the right frame of reference to appreciate it. But it still holds up as one of the great horror films of the 1920s; not particularly scary, but with a wonderful atmosphere that hangs between wonder and dread. Caligari is second only to Murnau’s Nosferatu.

I admire this film more than I enjoy it. However, I have nothing but love for that twist ending. It’s a masterful rug-pull that completely took me off-guard the first time I saw it, and still manages to somehow be surprising on rewatches.

JUSTIN HARLAN: I remember this one time I watched two supposedly important horror films in a row and found both to be total snoozefests. The first was Herzog’s retelling of Murnau’s Nosferatu and the second was this one. While I didn’t get through the first, I did make it through this one, at least. I see why it’s influential and I see some of the great things about it and all… but… zzzzzzZZZZZZzzzZZZZZZzZZzzzzzZZZzz…

JUSTIN HARLAN: I remember this one time I watched two supposedly important horror films in a row and found both to be total snoozefests. The first was Herzog’s retelling of Murnau’s Nosferatu and the second was this one. While I didn’t get through the first, I did make it through this one, at least. I see why it’s influential and I see some of the great things about it and all… but… zzzzzzZZZZZZzzzZZZZZZzZZzzzzzZZZzz…