31 Days, Day 29: 1963’s THE HAUNTING and the Challenge of Adapting Great Fiction

With the release of Mike Flanagan’s new Netflix series The Haunting of Hill House, Luke revives The Cinephile Files to explore Shirley Jackson’s classic novel, and its first screen adaptation: Robert Wise’s The Haunting, and examines the challenges that come from adapting a great work of fiction to another medium.

Adapting a great novel to the screen presents a challenge to the filmmaker; often the thing that makes a novel great doesn’t really translate to another medium, like film, because they are unique to the novel. Narrative functions the same way on both page and screen, which is why so many films are successfully adapted from novels, and why so many mediocre novels can be made into great films. But what novels offer is a specificity of language and the way in which it takes a reader inside its characters’ heads; maps out rich inner lives. Novel’s put their characters heads directly in your head.

Ultimately, the narrative of Haunting of Hill House isn’t particularly unique. It’s a pretty standard haunted house story; a professor and two assistants, along with the property’s heir, spend some time in a famous haunted house to investigate paranormal phenomena. The House, “not sane” as Jackson so succinctly puts it, begins to exert its evil power over them. What is special about Jackson’s novel is the psychological element; the inner life of its protagonist, Eleanor. A fragile woman, looking to start life over after years caring for her ailing mother, she answers the ad by Dr. Montague, to spend the summer investigating the strange goings-on in the uninhabited, 80 year old Hill House.

Jackson uses the mechanics of genre, to tell a familiar story in an unusual way. The novel successfully builds terror slowly by exploiting the reader’s understanding of haunted house tropes. We know the house is evil, we know that whatever haunts it will exact its price from the intruders. But what makes it unique is that she does so by telling the narrative through the perspective of Eleanor, and her deteriorating mental state. This gives the novel with an uneasy subjectivity, chipping away at the reader’s sense of the real and unreal. This effect is amplified by the masterful way Jackson subtly begins to dissolve Eleanor’s identity into that of the house, as if it consumes her.

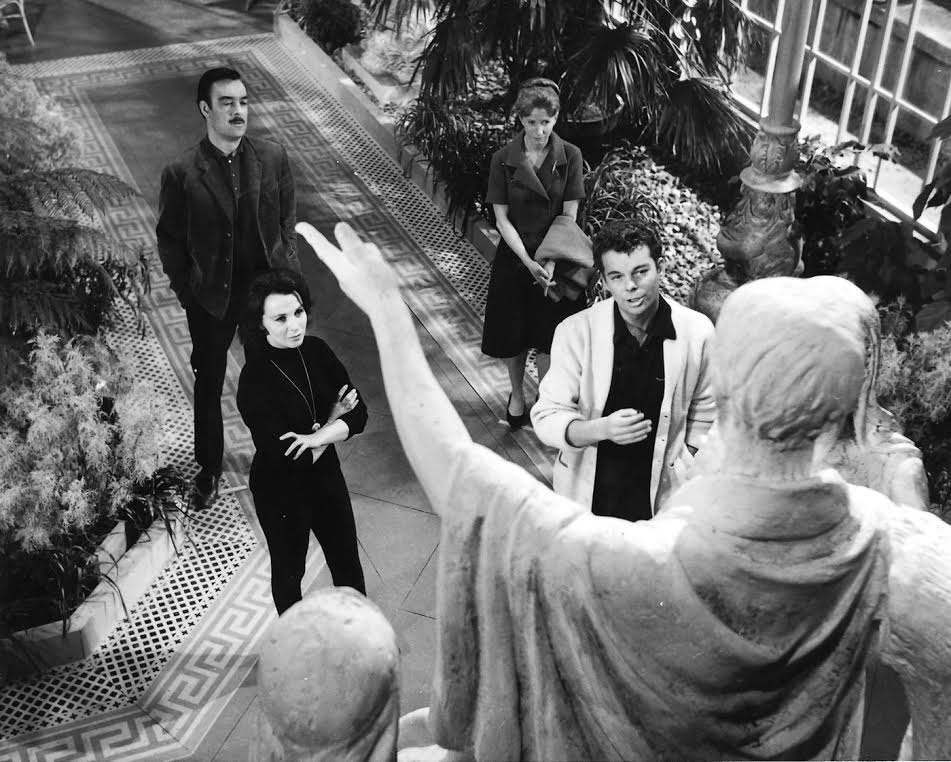

Directed by Robert Wise, the 1963 film adaptation a little disappointing. It’s well-made on a technical level, a faithful adaptation of the Jackson novel, handsomely shot in black and white. Yet, there’s a kind of stilted mustiness to it; it’s an old-fashioned, stylistically conservative Hollywood production by a career journeyman at a time when Hollywood – not to mention the culture at large – was undergoing radical changes. You could see it on the horizon, with Hitchcock’s Psycho in 1960 and Jack Clayton’s The Innocents in ’62. Horror movies were changing rapidly; evolving with the culture; feeding off of the anxiety in the air. You can see it in the self-aware cynicism towards decaying Hollywood glamor of the old era in Robert Aldrich’s Whatever Happened to Baby Jane. And let’s not forget that The Haunting was released a mere five years before the seismic shift to horror cinema brought on by George Romero’s Night of the Living Dead.

That leaves The Haunting as an also-ran; old-fashioned in its time, a nostalgic holdover of a dying era. It’s too competent to be camp, and a too stagey and melodramatic to be truly unsettling. But the biggest missed opportunity of the film is its failed attempt at adapting Eleanor’s inwardness. Nelson Gidding’s screenplay goes so far as to quote Jackson’s novel directly, making Eleanor’s thoughts a voiceover, but in the context of the film it comes off as a lazy short-cut, a film version of that old creative writing crutch, “telling, not showing”. The thought-bubble overdubs, complete with a hokey reverb effect, played over the furtive stares of Julie Harris’ Eleanor take the viewer out of the narrative. They tell you how to feel, instead of giving you the feelings first hand. It’s like being told someone else’s dream. Jackson’s novel is like having the dream yourself.